Google.gov: Part 1

From search engine to partisan.

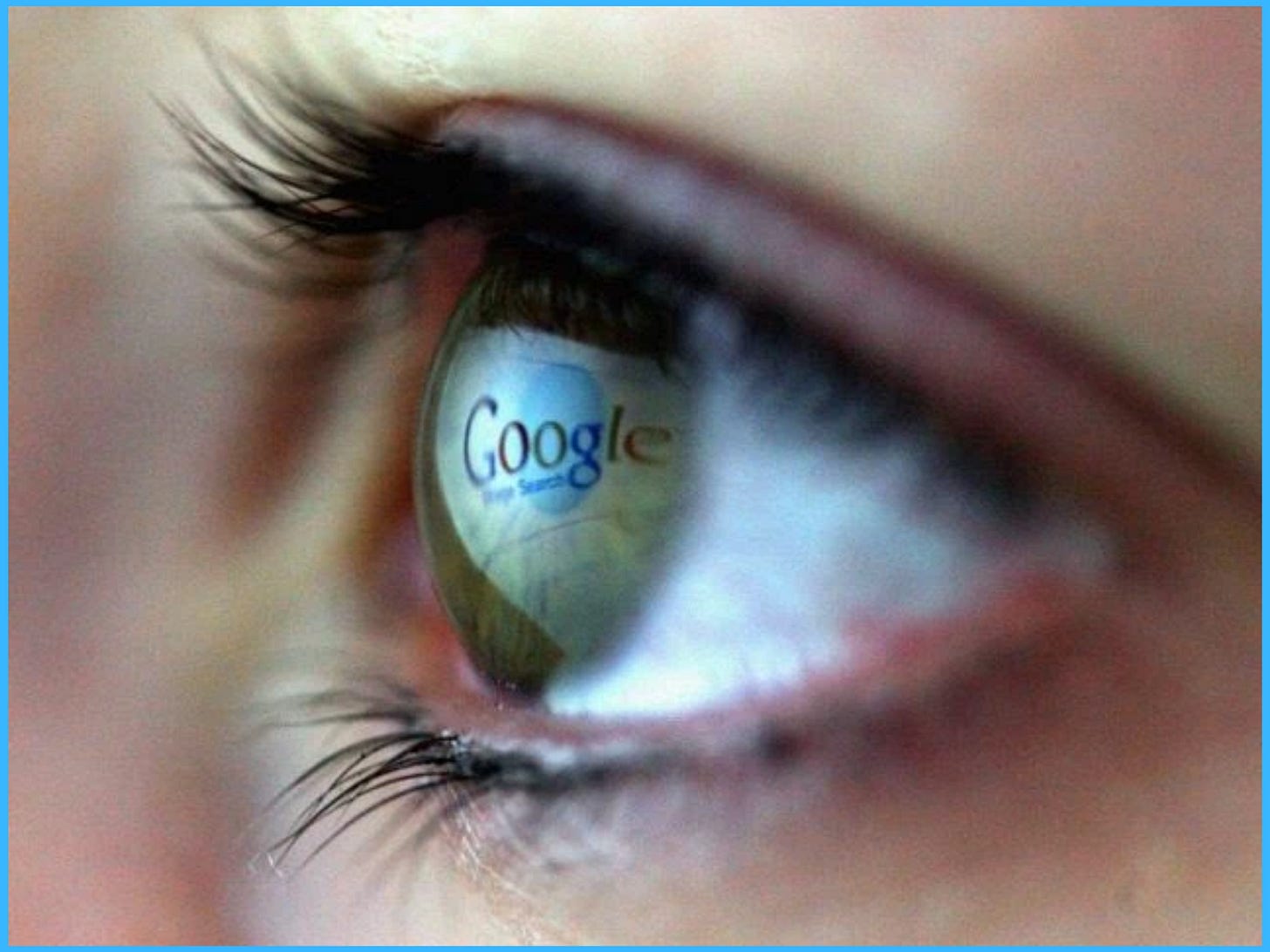

Omnipotent and Omniscient

Let’s get something out of the way: I appreciate Google’s products. Yours truly even has a Pixel 6. And frankly the search engine might as well be magic in my opinion. I use Google a lot, and I never fail to appreciate how incredible it is that any kind of mental itch I might have can be, well, itched—and in milliseconds, too.

That being said, I’m not exactly a big fan of the people of whom Google is comprised, for reasons that’ll soon become obvious.

There’s a tendency — a passive acceptance that belongs somewhere along a continuum between faith and negligence — to assume that the tech giant is merely a benign, disinterested gatekeeper of a vast repository of information. But nothing could be further from the truth. Google is arguably the most powerful entity in the history of mankind, and I hope to illustrate why while highlighting the implications in this post and a follow up.

To give you an idea of Google’s reach, some numbers and figures are in order:

Google handles more than 65,000 search queries a second. That’s 3.9 million a minute, 234 million an hour, 5.6 billion a day, and more than 2 trillion a year.

281 billion emails are sent on Gmail every day. As of 2018, Gmail had more than 1.5 billion users.

Google is by far the biggest mobile operating system in the world, with over 2.5 billion monthly active Google Android devices.

As of 2016 (the last time Google revealed this figure), Google’s search index included more than 130 trillion webpages. If you printed those pages on typical A4 paper that’s 0.05mm thick, you could stack those papers to the moon 17 times.

Today, Google’s search market share stands at 92.47%. For comparison, Yahoo!’s is 1.48%.

Google’s 2021 advertising revenue was $54.7 billion (up 22% from $44.7 billion).

YouTube, which Google owns, is the world’s second most popular search engine. As early as 2009, search volume on YouTube outstripped Yahoo!’s by 50% and Bing’s by 150%.

YouTube has more than 2.6 billion active users. 1 billion hours of content is watched across the world every day on the platform, and every single minute, more than 500 hours of new content is uploaded.

Data, data, data.

In recent years, as public concerns about Big Tech have become more pronounced, reporters and politicians alike have suggested that the traditional antitrust remedies of regulation or breakup may be necessary to rein Google in. As the starting point for billions of dollars of commerce, businesses, lawmakers, and advertisers are worried about fairness and competition within the markets where Google is top dog.1

The monopoly that Google enjoys is much different than monopolies of old—think Andrew Carnegie’s Steel Company (now U.S. Steel) or John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company. The product over which Google has a monopoly is us: Our attention, our personal information, our content—the three key ingredients for human manipulation in the 21st century.

The company is basically the Eye of Sauron, having expanded into services far afield from search while assembling the greatest surveillance network the world has ever seen. Even the consumer profiles acquired by Facebook pale in comparison with those maintained by Google, which is collecting information about people 24/7, using more than 60 different observation platforms—the search engine of course, but also Google Wallet, Google Maps, Google Adwords, Google Analytics, Chrome, Google Docs, Android, YouTube, and on and on. Few Gmail users are aware that Google stores and analyzes every email they write, even the drafts they never send—as well as all the incoming email they receive from both Gmail and non-Gmail users.

According to Google’s privacy policy — to which one assents whenever one uses a Google product, even when one has not been informed that he or she is using a Google product — Google is entitled to share all the data it collects about you with almost anyone, including the federal government. But never with you. Your privacy is not the priority; Google’s privacy, however, is sacrosanct.

You might well point out that nobody’s required to use Google and that there are other search engines available. “We do not trap our users,” Eric Schmidt, executive chairman of Alphabet, Inc., told a Senate subcommittee in 2011. “If you do not like the answer that Google search provides you can switch to another engine with literally one click, and we have lots of evidence that people do this.”

But not all search engines are equal. Far from it. Google’s first-mover advantage cannot be overstated, and it’s simply impossible to compete with the tech giant. Having accumulated nearly twenty years of data, its algorithms draw from a data set so comprehensive that no other search engine could ever imitate it. Eric Schmidt himself recognized this in 2003, when he told the New York Times that the sheer size and scope of Google’s resources was an insurmountable barrier to entry. And that was 19 years ago.

Moreover, Google’s algorithm is among the best-kept secrets in the world, on a par with the formula for Coca-Cola, and is vastly superior to that of competitors. The search engine is so good2 at giving us exactly the information we are looking for, and does it so quickly, that the company’s name is now a commonly used verb in languages around the world.

Google it.

“A digital Switzerland”

In the beginning, Google had the highest aspirations for its search engine: “A perfect search engine will process and understand all the information in the world,” co-founder Sergey Brin announced in a 1999 press release. “Google’s mission is to organize the world’s information, making it universally accessible and useful.”

As part of the initial public offering in 2004, the search engine’s founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, told investors that “Google is not a conventional company,” and that they would always put long-term values over short-term financial gain. “Making the world a better place” would be a primary business goal, and Google’s moral compass could be summed up in a simple and much ballyhooed motto: “Don’t be evil.”

The company has often stressed that its search results are superior precisely because they are based upon neutral algorithms unsullied by human judgment. As Ken Auletta recounts in his 2009 book Googled, Sergey Brin “explained that Google was a digital Switzerland, a ‘neutral’ search engine that favored no content company and no advertisers.”

Everyday people trust Google based on the understanding of this original mission to simply answer queries based on user priorities. But the Google of today is much different than the founders’ idealistic vision would have you assume, having crept toward a more tutelary role in shaping thought.

In the 2013 update of the Founders Letter, Page described the “search engine of my dreams,” which “provides information without you even having to ask, so no more digging around in your inbox to find the tracking number for a much-needed delivery; it’s already there on your screen.”

Page acknowledged in the 2013 letter that “in many ways, we’re a million miles away” from that perfect search engine—“one that gets you just the right information at the exact moment you need it with almost no effort.”

To say that the perfect search engine is one that minimizes the user’s effort is effectively to say that it minimizes the user’s active input. In this respect, Google’s aim is to provide perfect results for what users actually want—even if users themselves don’t yet realize what that is. In other words, the ultimate goal is not to answer a user’s question, but the question Google believes should have been asked.

Schmidt himself shared this same conclusion in 2010, as described in a Wall Street Journal article for which he was interviewed: “I actually think most people don’t want Google to answer their questions,” he said. “They want Google to tell them what they should be doing next.”

Google’s Foray Into China

In 2006, Google attracted strong criticism for censoring its search results at Google.cn to suit the Chinese government’s restrictions on free speech and access to information. As the New York Times reported, for Google’s Chinese search engine, “the company had agreed to purge its search results of any Web sites disapproved of by the Chinese government, including Web sites promoting Falun Gong, a government-banned spiritual movement; sites promoting free speech in China; or any mention of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.”

In his 2011 book In the Plex, Steven Levy recounts how Google executives used “moral metrics” to decide that the good Google might do for the people of China outweighed the bad that would come from banning content.3

The decision to appease China, temporary and tenuous though the relationship might’ve been, is revealing, as it confirms the company is willing to compromise the neutrality of its search results, and itself, for the sake of what it deems the “broader public good.”

This gets at the crux of the key issue I have: Whose definition of “public good” is Google operating under, and what happens if, say, the company were to cooperate with a government less adversarial and inflexible than China’s, whose conception of the public good it more closely shares?

Google could very well begin to embrace a role of actively shaping the informational landscape under the pretense of some “noble end.” In much the same way that Democrats have developed a penchant for suspending “the way things are normally done” (AKA the law) based on the pretext that extraordinary times call for extralegal measures (q.v. - Russiagate, fire bombing pro-life clinics, protesting in front of SCOTUS justices’ homes, pretty much every pandemic policy to include changing voting laws to allow for mass mail-in ballots and vaccine mandates, hiring people based on race and LGBTQ+ identity, flouting habeas corpus and due process, etcetera), so too might Google bend its own rules in support of what it considers the greater public good.

That’s essentially what’s happened.

“Money don't lie.”

Google has slowly but surely expanded its mission to include doing good, which is obviously another matter entirely and takes the company well outside the parameters of its original ideals, which was facilitating the free flow of information as a platonic overseer and civil servant.

This has occurred in tandem with the company’s increasingly obvious political allegiance. I’m not sure who needs to hear this, but the company very much beats the progressive drum. We’ll flesh this out more below (and especially so in part two of this post), but consider that in the 2004 election, a whopping 98% of the company’s employees gave money to the Democratic Party.

This was not an anomaly. In the 2012 presidential election, Google and its top executives donated more than $800,000 to President Barack Obama and just $37,000 to his opponent, Mitt Romney. Employees at Alphabet (Google’s parent company) and its affiliated organizations contributed nearly $22 million to Democrats during the 2020 elections compared to $1.4 million to Republicans, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. And this year, they’ve been flooding Democratic coffers in preparation for midterm elections: Google employees have provided $652,600 to Democrats and just $37,700 to Republicans, meaning that just over 94% of donations have gone to the former.4

“Money don't lie.”

Google shares an ethos and a worldview with the Democratic Party that intertwine and lead to the same conclusion: All of America’s problems can be answered via social engineering—a process that depends on facts and truth remaining, in the words of The New Atlantis’s Aaron White, “ruthlessly value-free and yet, when properly grasped, a powerful force for ideological and social reform.”

This follows with the progressive worldview more broadly that was all the rage during the Obama years, and which has since gone bat-shit crazy ever since the election of the Bad Orange Man w/Mean Tweets and the concomitant challenge to elites by populist psycho-social forces. The common theme (other than elitism) is that the demos make wrong decisions not because the world is as complex as ever or even for specific reasons but because they’re dumb and self-interested rubes that fail to listen to their betters.

Since calamity struck in 2016, many a progressive have convinced themselves — often with dogmatic certainty — of a long list of charitable interpretations upon which their self-perception depends (#ally), including that they're pro-facts and pro-science while everyone else is, by default, either a white supremacist or stupid, and perhaps even both. A shocking number still cling to the belief that Hillary Clinton lost not because Donald Trump won, but because a combination of Russian disinformation, fake news, and deplorables robbed HRC of her throne.

A central tenet of today’s progressive orthodoxy is that good governance requires well-informed choices. With respect to Google and information in general, this is not the same as giving people what they think they want. That would be foolish, since in this paradigm the layman’s untutored mind is Extremely Dangerous to Our Democracy™.

No, what progressives covet is the power to curate the informational landscape as they see fit (q.v. - Ministry of Truth) while palming it off under benevolent pretenses. Censorship, for example, isn't censorship at all, it’s merely the enforcement of a “well-ordered space for safety and civility” by the platforms themselves.

It reminds me of the scene in the first season of The Office where they’re playing basketball against the warehouse workers to determine who has to come in on Saturday. Michael gets hit in the face, and he says the game’s over because it was a flagrant foul. When the warehouse workers ask him who wins then, Michael says whichever team was up last knowing full-well that his team is up, but of course he pretends he had no idea.

That’s the same kind of chicanery at play here when it comes to the left-wing argument that Big Tech platforms should be allowed to censor in order to stop misinformation and hate speech, which we all know are umbrella terms for “stuff the Left doesn’t like.”

Okay, we need to censor to protect the docile masses, guys, so who’s in charge at Google et al.?

Progressives.

Really? Oh, wow. Well, that’s totally irrelevant. We’ll be sure to keep our infamously unyielding ideology from having an impact on decisions. Promise.

The Obama Administration

Google’s affinity with progressive politics was especially pronounced during Obamamerica. In November 2007, the former president chose Google’s HQ as the forum to announce his nascent presidential campaign’s “Innovation Agenda,” a broad portfolio of policies on net neutrality, patent reform, immigration, broadband Internet infrastructure, and governmental transparency, among other topics. His remarks that day emphasized how closely aligned he believed his vision was with Google’s:

“What we shared is a belief in changing the world from the bottom up, not the top down; that a bunch of ordinary people can do extraordinary things … the Google story is more than just being about the bottom line. It’s about seeing what we can accomplish when we believe in things that are unseen, when we take the measure of our changing times and we take action to shape them.”

After Obama’s speech, Eric Schmidt joined him on stage to lead a meandering Q&A. In the closing minutes, Obama addressed a less obvious issue—the need to use information technology to correct people’s misinformed opinions:

“You know, one of the things that you learn when you’re traveling and running for president is, the American people at their core are a decent people. There’s . . . common sense there, but it’s not tapped. And mainly people—they’re just misinformed, or they’re too busy, they’re trying to get their kids to school, they’re working, they just don’t have enough information, or they’re not professionals at sorting out the information that’s out there, and so our political process gets skewed.

But if you give them good information, their instincts are good and they will make good decisions. And the president has the bully pulpit to give them good information … I want people in technology, I want innovators and engineers and scientists like yourselves, I want you helping us make policy—based on facts! Based on reason!”

As Matthew B. Crawford aptly notes, Obama’s “bully pulpit” reference was telling. The pulpit is normally used to persuade, but Obama averred that he’d use it to “give good information.” Persuasion is fundamental to politics. Curating information, however, is something you do if your perspective is one from which dissent can only be prima facie evidence of someone’s thought process perverted by malignant actors and misinformation.

Well, Google execs sure followed through on Obama’s request for assistance. Not only did Eric Schmidt endorse Obama and campaign for him, but according to a 2013 Bloomberg report, Google’s data tools helped the Obama campaign cut their media budget costs by tens of millions of dollars through effective targeting. Schmidt even helped make hiring and technology decisions for Obama’s analytics team.

But the Google-Obama relationship wasn't limited to campaigns. A partnership between the two, largely unnoticed by the wider public, was established while Obama was in office.5 In October 2014, the Washington Post recounted the migration of talent from Google to the Obama White House under the headline, “With appointment after appointment, Google’s ideas are taking hold in D.C.”

That’s one way of describing it. But I’d say that the relationship was comparable to the revolving door between the FDA and Big Pharma. The extent of the kinship wasn’t fully explored until 2016, when The Intercept published “The Android Administration,” an in-depth exposé detailing how “no other public company approaches this degree of intimacy with government.” According to the report:

No fewer than 55 Google employees left the company to take positions in the Obama administration, while 197 government employees moved from the federal bureaucracy to Google or to other companies and organizations owned by Eric Schmidt. To get a sense of how crazy these numbers are, as of 2020 there were 377 people employed in the West Wing.

There were seven cases of “full revolutions through the revolving door”—individuals who either went “from Google to government and back again, or from the government to Google and then back again.”

427 meetings between the White House and Google employees took place from 2009 to 2015—more than once a week on average. The New Atlantis’s Aaron White pointed out that the actual number of meetings is likely even higher, since, according to reports from the New York Times and Politico, White House officials made a habit of conducting meetings outside the grounds to skirt disclosure requirements.

This harmonious relationship between Google and the Democratic Party was poised to continue through 2016. Leaked emails from WikiLeaks revealed that ol’ Eric Schmidt was practically embedded in the Clinton campaign, giving HRC advice and support, but also helping with design, finances, and implementation of the campaign’s digital voter-targeting operation. Internal campaign emails released by WikiLeaks show that Schmidt met with the team working on Clinton’s incipient campaign on April 2nd and 3rd, 2014, before it was even announced. One leaked email from Clinton campaign manager John Podesta said that Schmidt “clearly wants to be head outside advisor,” and at Clinton’s election night party in New York City, Schmidt was even spotted wearing a Clinton “staff” badge. Staff.

It’s no secret that big banks like Goldman Sachs have long benefited from placing former employees in senior White House positions, but when it comes to Google and Silicon Valley in general, there are two big concerns here. Number one, if Big Tech maintains a symbiotic relationship with the White House, there’s a very good chance that it’ll lead to favorable policy decisions.6 Remember “net neutrality”? That Obama-era policy favored Google to the detriment of telecom companies like Verizon. And number two, I highly doubt that anyone who cares enough about politics to work with a specific presidential administration/campaign is going to ditch that partisan jersey. If anything, they’re just going to wear that same partisan jersey underneath a button-up or whatever the hell the wonks at Google wear.

The follow-up to this post will explain in detail why all of this is troubling, but it’s not hard to see how even seemingly innocuous internal decisions at Google could have profound political consequences. The search engine’s ability to index and rank certain sources above others directly influences the exploratory framework of a user. In Silicon Valley parlance, such an ability is called a “nudge.”

In their eponymous book, Nudge, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein explain how the particular ways in which information is presented is a central aspect of “choice architecture.” As they put it,

“. . . public-spirited choice architects — those who run the daily newspaper, for example — know that it’s good to nudge people in directions that they might not have specifically chosen in advance. Structuring choice sometimes means helping people to learn, so they can later make better choices on their own.”

Take this concept from a micro perspective (the “public-spirited” publisher of a daily) and expand it to the macro (Google’s search engine). Imagine, then, the impact Google might have in something as consequential as a national election.

With over a 92% market share of all search engine queries, Google is the defacto gateway to the internet. Combine its “nudge” potential with the company’s ability to rank, index, and even “blacklist” websites, and Google effectively has the power to tailor how the internet appears to people.

Moreover, as Google execs become accustomed to making decisions based on a sense of obligation that goes beyond providing neutral service and products, and as progressive pols increasingly see Big Tech as an instrument to be wielded in shaping (and limiting) public discourse, the slippery slope cants toward an obvious outcome: Google proactively employing its power to advance its definition of “the public good,” which yours truly would bet dollars to donuts coincides with progressive orthodoxies.

As we’ll see in part two of this post, it’s already happening.

These worries are not unfounded. In the European Union, the company has been fined more than $9 billion in the past three years for anticompetitive practices, including using its search engine to favor its own products.

About 50% of our clicks go to the top two items, and more than 90% of our clicks go to the 10 items listed on the first page of results.

In 2010, Google announced that it had discovered an “attack on our corporate infrastructure originating from China” and that a main target was the Gmail accounts of Chinese human rights activists. After this, the company told China it would no longer censor any content in the country. Google search has now been blocked in mainland China since 2014, along with many other Google services.

At Twitter, 99% of employee donations have gone to Democrats.

Recall that during these years, Google became aligned with progressive politics on a number of issues—net neutrality, intellectual property, payday loans, and others.

Google’s extraordinarily close relationship with President Obama’s administration led to a long list of policy victories of incalculable value to its business.

"In other words, the ultimate goal is not to answer a user’s question, but the question Google believes should have been asked." That's the crux of the problem. It allows any and all sorts of mischief, because algorithms are created by fallible people, not delivered by some infallible higher power.

In using search engines, Google or not, the first problem is knowing how to form a proper query. That is a skill few people have. I laugh every time someone demands I give them a link. As I refine my query (the first one is often too broad) I finally bring the number of answers down to fewer than ten million. Even then, any information that is not unabashed PR for the Democratic Party is located on page 27 and later.

Few people have the patience to go through 27 or 107 pages of articles seeking out the dots to connect. It's why the reason for the 2008 crash is so hard to find. Yes, it was George W. Bush's fault, but not for the reasons portrayed. He used the Community Reinvestment Act to try and boost minority home ownership. The way in which it was executed was a catastrophe. Once the truth is elicited the primary villain emerges: Dr. Franklin Raines, Chairman of Fannie Mae.

Its accounting would have been more honest if they'd used Enron's folks. Every quarter, like clockwork, the numbers equated to the mill what was needed to trigger bonuses for the senior staff. He was punished by being named Obama's chief financial advisor for the 2008 campaign.

Compelling writing!

I may be one of the Deplorables, but my question is: Even if we like the progressive agenda, how do we prevent the kind of abuse you document?