What Patriarchy?

How males are being left behind.

This is a subject that I’ve written about before, but which I think still requires far more attention than it’s getting.

In mainstream culture, the struggle for female equality continues to be portrayed as a slow, laborious game of catch-up in the form of social, political, and economic changes. The dominant narrative of gender equality is framed almost exclusively in terms of the disadvantages of girls and women.

But this framing belies a remarkable, seismic shift in the West, particularly in America: It’s no longer a man’s world. “The 200,000 year period in which men have been top dog is truly coming to an end,” writes Hanna Rosin in The End of Men. “The global economy is becoming a place where women are more successful than men.”

Today, women are doing better than men in almost every key metric, in large part because modern society is better suited to the former. This doesn’t seem to be lost on parents-to-be. In the past, most dads wanted their first child to be a son. No longer. Today, dads-to-be are almost twice as likely to prefer a daughter to a son, while moms-to-be are 24% more likely to prefer their firstborn child to be a daughter.

To countenance this strange new reality might very well induce ideational vertigo, as it challenges conventional wisdom about gender. But once you’re willing to dispense with stereotyped assumptions and entertain the possibility, you’ll find evidence that this has been a long time coming. For the last half-century, the Western world has been fixated on maximizing female empowerment, so much so that a political climate has emerged in which highlighting the problems of boys and men is all but taboo. In the process, our understanding of men regressed and a “boy crisis” emerged that’s still seldom acknowledged.

A Changing Economy

For decades, men have been losing ground in the labor market—not because of a decline in work ethic or widespread “male malaise,” but because of shifts in the structure of the economy and the inexorable forces of modernization.

Traditionally male jobs have been gutted by free trade and technology. Machines pose a greater threat to men than women because the occupations most susceptible to automation are just more likely to employ males. According to the Brookings Institution, men “make up over 70 percent of production occupations, over 80 percent of transportation occupations, and over 90 percent of construction and installation occupations.” The Great Recession served to accelerate a profound economic shift that had been occurring for at least thirty years, and in some respects even longer, and it dealt a terrible blow to men, who lost three-quarters of the 8 million jobs purged from the economy. The worst-hit industries were overwhelmingly those that deeply identified with masculinity, including construction, manufacturing, and finance.

Today, women make up most of the workforce in the service and information economy, which is relatively automation-safe and “robot-proof.” Whereas men’s size and strength were once the more valuable attributes in the industrial economy, today’s postindustrial economy is indifferent to brawn and instead puts a premium on what Susan Faludi calls “ornamental culture,” which is driven by commercial values like social intelligence, communication, and the ability to sit still and focus—attributes that can’t be easily replaced by a machine.

Andy Haldane, chief economist at the Bank of England, has noted that “the high-skill, high-pay jobs of the future may involve skills better measured by EQ (a measure of emotional intelligence) than IQ.” Historically, these “soft skills” have been more associated with — and encouraged in — women, giving them a considerable leg up in the labor market. In the U.S. since the 1980s, the likelihood of a college-educated man ending up in a highly skilled cognitive occupation has fallen, while the likelihood of a college-educated woman achieving the same feat has increased.

Moreover, after correction for inflation, the median wages of American men have been stagnant for half a century. Only men at the top rungs of the social ladder have seen strong earnings growth. But for those without a four-year degree, median earnings lost 13% of their purchasing power between 1979 and 2017. Over the same period, national income per capita grew by 85% and women’s wages rose across the board.

It’s imperative that men be helped to adapt to a labor market undergoing a radical transformation, and yet this urgency isn’t reflected in public policy initiatives. Indeed, there are no such initiatives; it is only women whom the government is concerned about. This, even though the occupations set to grow the most in coming years are female dominated, and even though for over a decade now the balance of the workforce has been tipped toward women, who now hold a majority of the nation’s jobs.

Men without prospects do not make good marriage partners, and with the rise in female earning power, men need to clear a higher bar to be seen as husband material.1 Without a job that can provide for a family, they become less marriageable, and one of the pillars of a stable life moves out of reach. Particularly among less educated whites, marriage rates have fallen and more men have lost out on the benefits of this institution, of seeing their children grow and of knowing their grandchildren. The Atlantic pointed out over a decade ago that the working class, which has long defined traditional understanding of masculinity, has slowly turned into a matriarchy, with men increasingly absent from the home and women in charge. Though certainly empowering for women, in the long run this does not portend well. We know that children, especially boys, who grow up without a steady father figure can suffer lasting damage. They’re more likely to end up in poverty or drop out of school, become addicted to drugs, have a child out of wedlock, or end up in prison.

The Education Gap

The U.S. economy continues to shift to service-providing industries, where women traditionally work. Those jobs require more education, leaving males at a severe disadvantage, whose relative underperformance in the classroom badly damages their prospects for employment and upward economic mobility.

Boys are 50% more likely than girls to fail at all three key school subjects: Math, reading, and science. Girls are 14 percentage points more likely than boys to be “school ready” at age 5, controlling for parental characteristics—an even bigger gap than the one between rich and poor children, or black and white children, or between those who attend preschool and those who do not.

A national study conducted by Stanford scholar Sean Reardon found no overall gap in math from grades three through eight, but a formidable one in English. “In virtually every school district in the United States, female students outperformed male students on ELA [English Language Arts] tests,” he writes. “In the average district, the gap is … roughly two thirds of a grade level and is larger than the effects of most large-scale educational interventions.” A 6-percentage-point gender gap in reading proficiency in fourth grade widens to a 11-percentage-point gap by the end of eighth grade.2

The female lead in education is all but solidified by high school, where the decline of vocational training is robbing less academically-oriented boys of a feeling of productivity and competence. The most common high school grade for girls is now an A; for boys, it’s a B. Ranked by GPA, girls now account for two-thirds of high schoolers in the top 10% of classes, proportions that are reversed in the bottom percentile. Girls are also much more likely to be taking Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate classes.

The reasons behind these disparities vary depending on which way you frame the issue, but arguably the most clear-cut explanation has to do with neuroscience. It’s simple, really: Boys’ brains develop more slowly, especially during the most critical years of secondary education. The prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for impulse inhibition, critical thinking, attention, prospective memory, and planning, matures about 2 years later in boys than in girls. It may not be until late adolescence or their early 20s that boys’ brains catch up to their girl peers, and the gap in the development of skills and traits most important for academic success is largest at around the age of 16.3

In other words, the sexually dimorphic trajectories of the brain are furthest apart precisely when adolescents need to worry most about GPA, test scores, and checking inhibitions. It’s small wonder that nationwide, girls make up 70% of valedictorians, while boys get 70% of D’s and F’s.

“Because college preparation and applications must be done by teenagers, small differences in development can lead to large disparities in college outcomes,” write Claudia Goldin, Lawrence F. Katz, and Ilyana Kuziemko, in “The Homecoming of American College Women: The Reversal of the College Gender Gap.”

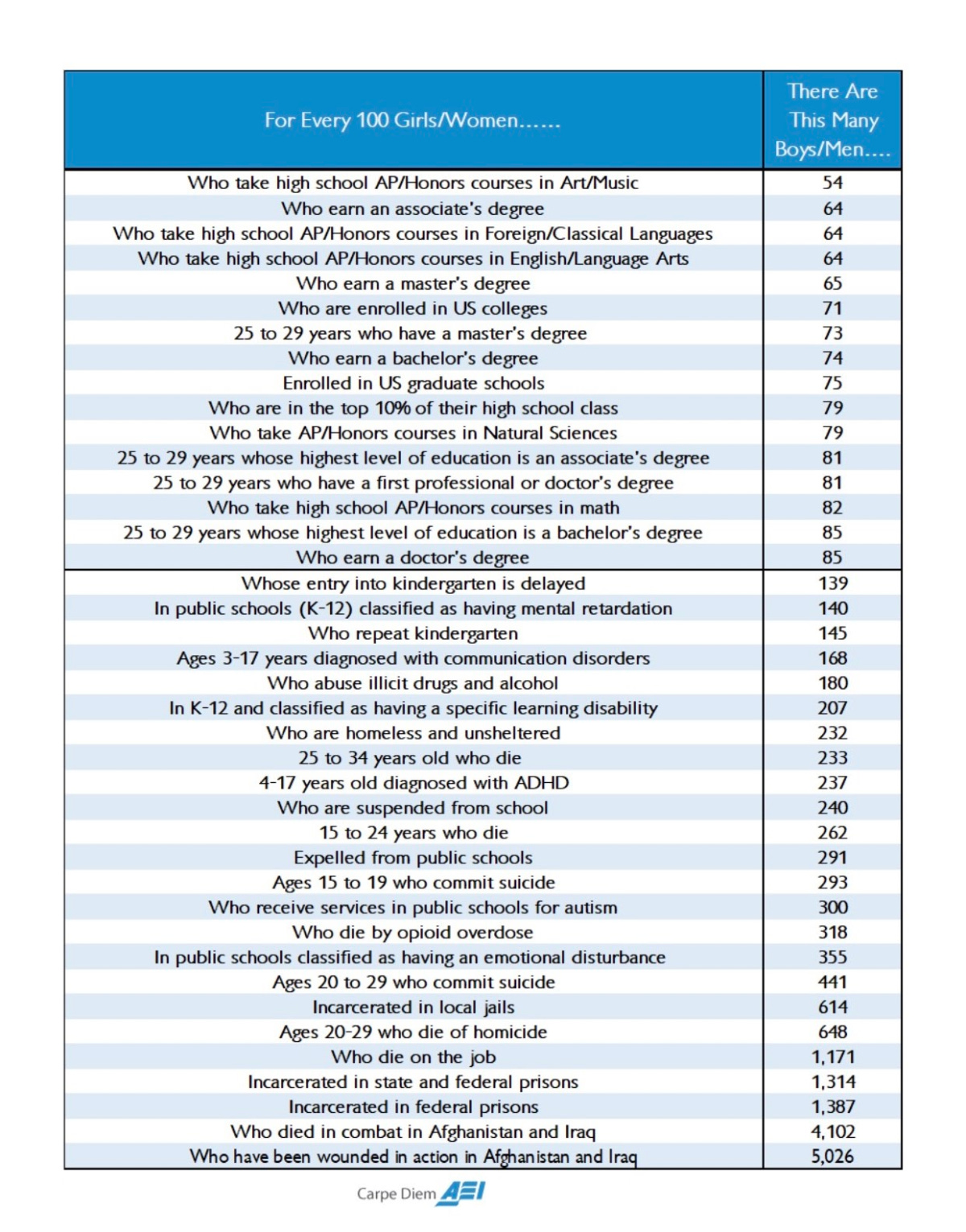

Indeed, the gender divide widens further in higher education, and the disparities at the college level largely reflect the ones in high school. It follows, then, that women are dominating college enrollment, a trend which peaked during the pandemic. In the U.S., for example, the 2020 decline in college enrollment was seven times greater for male than for female students. For every 100 bachelor’s degrees awarded to women, 74 are awarded to men. The grad school ratio is even worse. In my program (Strategic Public Relations) at USC, there were just over 50 students; four were males, including me. While that discrepancy may be a more extreme example, the Wall Street Journal revealed that men today make up only two out of five college students, and the men who do enroll are less likely to graduate than women.

Brookings scholar Richard Reeves writes, “In fact, taking into account other factors, such as test scores, family income, and high school grades, male students are at a higher risk of dropping out of college than any other group, including poor students, Black students, or foreign-born students.”

As of yet, there has been no revision or rethinking of educational policy or practice to address the lagging educational prospects for males. Indeed, government help remains almost exclusively for women,4 in large part because the Left fails to recognize that gender inequality is a two-way street. Consider: In 2021, Biden created a White House Gender Policy Council “to guide and coordinate government policy that impacts women and girls.” Last October, the Council published the first ever National Strategy on Gender Equity and Equality, in which not a single gender inequality related to males is addressed.

The pandemic illustrated how lopsided the moral imperative of female precedence has become. It is a rarely acknowledged fact that men are considerably more vulnerable to covid than women. Globally, men were around 50% more likely to die from the virus. In fact, per the Brookings Institution, for every 100 deaths among women aged 45–64, there were 184 male deaths. The disparity was so great that the average predicted life span for American men was cut by 2 years. In the UK, the death rate among working-age men was twice as high as for women of the same age. And yet, I imagine that you’d be hard-pressed to recall a single instance of the media, public health officials, or policymakers acknowledging this imbalance. During the rare times that it was noted, it was attributed to personal choices and the tendency of men “to engage in more risky behavior such as ignoring physical distancing.” (This is false; the mortality gap is based on biology.)

Across the board, people seemed entirely preoccupied with the pandemic’s impact on women and totally unconcerned with how men were faring. It started with the White House and its National Strategy on Gender Equity and Equality, which declared that “the COVID-19 pandemic has fueled a health crisis, an economic crisis, and a caregiving crisis that have magnified the challenges that women and girls … have long faced.”

And of course the media had a field day with overwrought lamentations about the pandemic’s “devastating” impact on women’s progress, rarely providing concrete evidence of the purported regression. “Covid-19 crisis could set women back decades, experts fear,” read one headline from the Guardian. “Why have women been so disproportionately affected by Covid-19?” CNN asked. “One of the most striking effects of the coronavirus will be to send many couples back to the 1950s,” wrote The Atlantic’s Helen Lewis, adding, “Across the world, women’s independence will be a silent victim of the pandemic.”

But nary a mention about the much higher risk of death for men, or the precipitous decline in college enrollment among males, or the desperate struggles of male breadwinners suddenly out of work and unable to provide for their families.

Toxic Masculinity is a Toxic Concept

Under the lens of progressivism and the Left’s decades-long effort to upend age-old verities and pathologize naturally occurring aspects of masculine identity, “toxic masculinity” is now so broadly applied that it’s essentially become an umbrella term under which is swept all manner of undesirable behavior on the part of boys and men. According to sociologist Carol Harrington, the term was rarely used before 2015; the number of articles never exceeded twenty, and almost all mentions were in scholarly journals. But after Trump’s ascendancy and the #MeToo movement, progressives brought it into everyday use.

Harrington notes that there remains no coherent or consistent definition, even within academia. Rather, the phrase is instead used to “signal disapproval.” This reductive tendency to so categorically deconstruct male behavior has resulted in toxic masculinity being blamed for everything from Brexit and climate change to financial crises and the election of Donald Trump. According to Peter Glick, a social psychologist at Lawrence University in Wisconsin, 2020 was a miserable year not because of the pandemic or the summer of love or an increase in vitriolic partisanship, but because of toxic masculinity. Fascinating.

The liberal postmodernist obsession with all things oppression leads them to wage war on oppressors real and imagined, and in so doing they invariably become oppressors themselves. The “fight against the patriarchy” and the stigmatization of men is a prime example. Infamously, Hillary Clinton spoke at a May 2017 Planned Parenthood gala where drinks called “toxic masculinity” were served. She explained that men are “doing everything they can to roll back the rights and progress we’ve fought so hard for over the last century.” Meanwhile, in academia, the only university courses on male-female relations — women’s and “gender” studies — teach students to view men as women’s oppressors.

The glib way with which the entire male sex is associated with behavior perceived as undesirable is part of a wider pattern of problematizing men and intensely scrutinizing everything they do so as to confirm a negative, preset perception. Consider the contrast between the ways women are encouraged that they can do anything they set their minds to (absolutely true) and how men are dismissed as barriers to progress and masculinity itself is deemed something to be avoided, or at least subdued. Treating males as though there’s something intrinsically, fundamentally tyrannical or toxic about them that must be exorcized is a recipe for resentment. The normalization of this paradigm, which is often borderline misandrist, is likely to bring out the worst in some men, not improve anything.

“The toxic masculinity … framing alienates the majority of nonviolent, non-extreme men,” feminist writer Helen Lewis says, “and does little to address the grievances, or counteract the methods, that lure susceptible individuals toward the far right.” According to a survey by the Public Religion Research Institute, half of American men and almost a third of women (30%) now believe that society “punishes men just for acting like men.”

Now, the naïve optimism of progressivism has led some people to not only regard normal male attributes as regrettable genetic defects, but to believe it’s possible to eradicate “destructive male tendencies” by essentially rewriting human nature. Undaunted by the endeavor’s self-evident futility, the Left is pushing emasculation as a solution, as if men are acculturated into maladaptive behaviors that can be excised by binding themselves to a severe morality. It’s not an insoluble cosmic mystery as to why this is a terrible idea and incredibly harmful to the developing psyches of young men, freighting them with the presumption that there’s something inherently wrong with being a male and that it must be guarded against. That’s psychoanalysis 101: If you repress something, it comes back with a vengeance.

Moreover, the idea of “masculinity” cannot exist except in contrast with “femininity.” The relationship is one of yin and yang, so to speak. To feminize masculinity is to run contrary to nature itself, for which all of society will suffer the long-term consequences in myriad little ways—paternally, economically, and perhaps even politically. If men feel unmoored, dislocated, and demeaned, they’re more likely to be receptive to reactionary political movements and Literal Fascism™.

In the lead up to the 2016 election, anthropologist Jennifer Silva spent some time in Coal Brook, Pennsylvania, where “massive transformations in gender, work and family … have ripped open men’s lives and left them scrambling to put them back together.” She noted that Donald Trump was widely, positively viewed as a “man’s man,” and that many men in Coal Brook were struggling to “sustain the masculine legacy of provision, protection, and courage that they inherited.” Others sought alternative ways to substantiate their masculine identity, and in the process of trying “to piece the self back together,” succumbed to the temporary relief of poisonous ameliorators.5

The bottom line is that the concept of toxic masculinity and the way it’s used to describe an overly-broad range of male behaviors and justify unnecessary social conditioning is itself toxic and leaves boys and men alike with a haphazard sense of self during a time when they’re increasingly devoid of identity and purpose.

The notion that Western society is a male-dominated patriarchy is still widely accepted without giving any thought to whether or not it’s accurate in 2023.

Yes, it’s true that most wealth is owned by men. Yes, it’s true that mass shooters are almost always men.6 Yes, it’s true that the vast majority of rapists are men. But so, too, is it true that a huge proportion, if not majority, of people who are seriously disaffected are men; most people in prison are men; most people who are homeless are men; most victims of violent crime are men; most people who kill themselves are men; most people who die in wars are men; and most people who die young are men. The “patriarchy” isn’t nearly as dominant as it’s made out to be.

Sure, there might be more men than women on the upper rungs of the social ladder, but that has no bearing on whether males more generally are struggling in modern society, and given the significant progress made by women in recent decades and the challenges now faced by many males, it makes no sense to treat gender inequality as a one-way street. Doing so contributes to the misguided zero-sum thinking that’s led progressives to act as though even acknowledging the problems of boys and men is to rob girls and women of their due attention.

Luckily, there are signs that this budding “boy crisis” is becoming a more salient issue. Liberal and conservative Americans alike are in general more worried about the prospects for boys than for girls, and for their own sons more than their own daughters, according to new data from the American Family Survey. Whether or not this has any impact on the prevailing progressive zeitgeist that reigns supreme in American institutions remains to be seen, but helping men find their footing in a world in which social roles are becoming increasingly blurred is not to disadvantage women. It’s possible to hold two thoughts in one’s head at the same time; we can emphasize women’s rights while still focusing on men struggling to adjust to a new social script and widespread anomie, and we can maintain a positive vision of masculinity compatible with gender equality without upending the progress women have made.

Even many men who are married are not ideal mates. Wives are twice as likely to initiate divorces as husbands.

Reading and verbal skills strongly predict college-going rates, and these are the areas where boys are furthest behind.

Adolescent girls also consistently score higher than boys on personality traits that are found to facilitate academic achievement.

Research shows that 92% of sex-specific scholarships are reserved for women.

Men account for close to three out of every four “deaths of despair”—suicide and drug overdoses.

This has everything to do with the “boy crisis.” These shooters are related in more ways than not. Most have grown up without a father figure; they have profound self-esteem issues; they feel unmoored from their peers and society; they’re lonely; and their lives are so devoid of meaning and purpose that they become nihilistic—when nothing matters, nothing matters.

Somebody please explain why in Finland, a country with some of the most progressive women's rights, more educated women chose to be stay at home mothers, and people are still getting married and having families. Finland polls as one of the happiest places. Young people in the US are depressed and suicidal.

I think there is more going on that just the economic changes. I think the cultural Marxists in control of our institutions have been pushing an ideology into primarily female student heads and the result is that more females dislike males, and more males dislike females. I think this change is by design by American feminists.

I once has a role in admission to grad. school. I noticed that a surprising number of men had good GREs but low GPAs because of poor grades the first two years of college. I decided to only look at the second two years and things evened out and we were able to admit more males. This was not a policy but something I did in one place.

But it was a pattern I observed.