How the Mainstream Media Commodified Polarization

The media system based on soliciting the audience’s support manufactures anger and outrage.

Trust in the mainstream media has hit an all-time low. The most commonly cited reasons for this are bias and fake news, but the real issue is that polarization has become a condition of their business success and thus systemically embedded in their business model. Indeed, a recent study found that America’s media environment is more polarized than any other Western country.

Not too long ago, journalism was the product of an ad-funded news media. The marketplace dictated that revenue from copy sales was insufficient to maintain news production, and so news outlets needed to attract advertising. Those that tried to rely on the reader’s dime eventually died out; those that focused on the “buying audience” — the affluent middle class — received money from growing advertising and thrived. As media ecologist Andrey Mir writes, the ad money didn’t tell the media what to cover, it just chose the media that encouraged its audience to buy goods and established a “supportive selling environment.”1 Media critics Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky argued that this allocative control influenced discourse formation by maintaining a context favorable to consumerism, social coherence, and political stability, and thereby “manufactured consent.”

One of the key tenets of ad-funded journalism was leaving judgement to readers. Advertising money made the media industry, in general, more politically neutral because bias would have repelled readers with opposite views and diminished audience size. In seeking the broadest audience possible to appeal to advertisers, publications made it known to journalists that they were not at liberty to indulge their own political preferences in their reporting, and that potentially divisive issues were to be avoided.

This significantly tamped down the public’s political fervency, depoliticizing society. Participation in elections fell so low that media historian Robert McChesney described America as a “democracy without citizens.” But polarization in society was also at a low point, even as the influence and prosperity of the mass media were at an all-time high.2 Political tranquility was a side effect.

To be sure, ad money carried its own risks, namely advertisers pressuring news production. This would have obviously undermined newsroom autonomy, which used to matter.

To protect journalism from advertisers and establish the credibility of news coverage, industry-wide professional standards were established. This was a period when reputational capital was a commodity. “The theory underlying the modern news industry has been the belief that credibility builds a broad and loyal audience, and that economic success follows in turn,” declared the American Press Association in its 1997 “Principles of Journalism” statement. Standards of objectivity, nonpartisan reporting, facts over opinions, and other guarantees enshrined in the ethical and professional codes of news organizations ensured that newsrooms remained independent.

These same professional standards allowed journalism to be treated as a public service. “The central purpose of journalism is to provide citizens with accurate and reliable information they need to function in a free society,” claimed the American Press Association’s statement. “Commitment to citizens also means journalism should present a representative picture of all constituent groups in society. Ignoring certain citizens has the effect of disenfranchising them.”

Journalism as an institution and the news as an industry peaked at the end of the 20th century, a time when even regional newspapers such as the Baltimore Sun possessed several well-staffed foreign bureaus. It was the Golden Age of ad-based media.

But the internet, with its digital tsunami of information and emancipation of authorship, shattered this idyll, crippling the traditional newspaper business model and the elite-controlled dispensation that had long endowed newsrooms with a sacrosanct authority as a gatekeeper to knowledge with a monopoly over dissemination and agenda-setting. A deafening Babel of voices now contradicts and drowns out everything the elites say, undermining their authority.

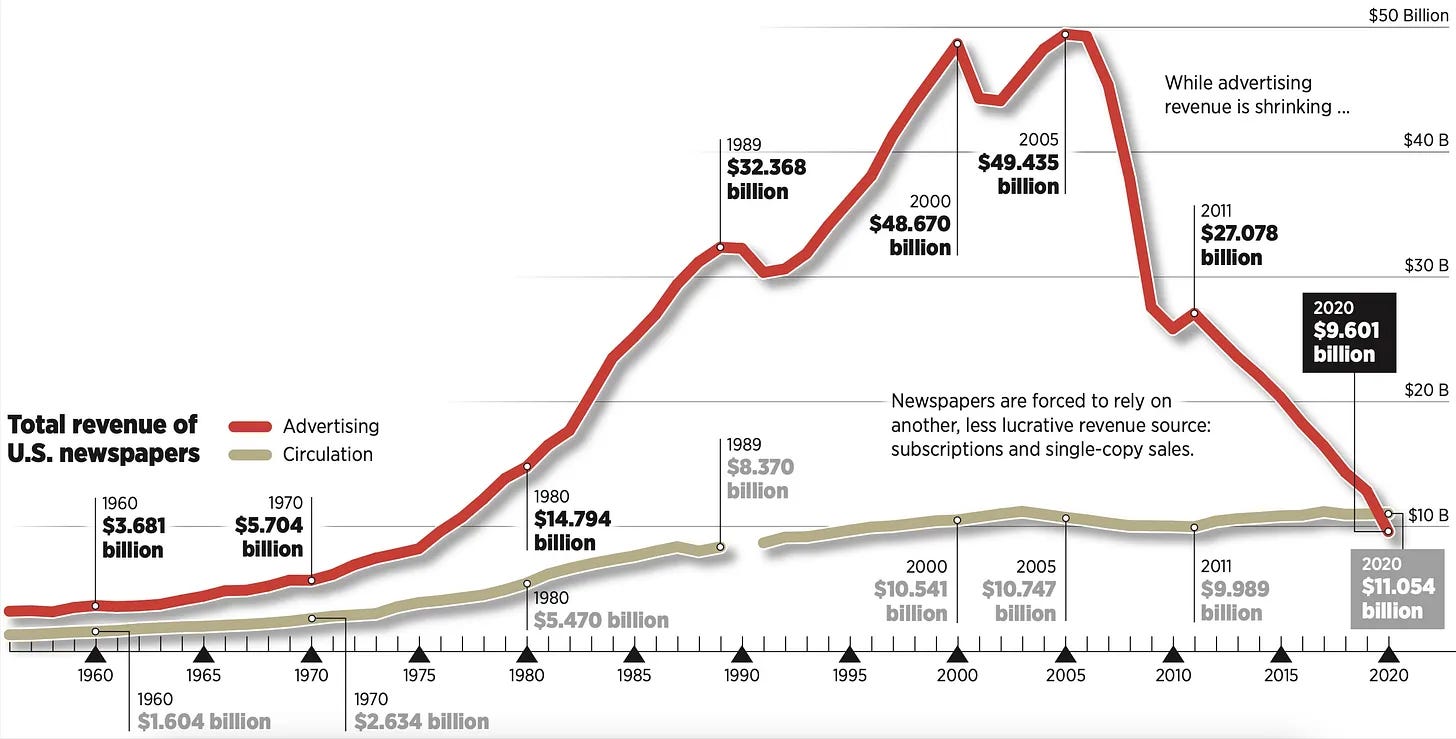

Advertisers and audiences have fled to better platforms like Facebook and Google, where content is free and more attractive and ad delivery is cheaper and more efficient. According to a 2021 study by the Pew Research Center, newspaper advertising revenue cratered from $49.4 billion in 2005 to $9.6 billion in 2020, and the hemorrhage continues to this day.

Ad revenue declined faster than reader revenue, and it soon became clear that it wouldn’t be possible to subsist on print subscriptions and newsstand copies. Newsrooms were suddenly forced to chase readers. Led by the New York Times, a few prominent brand names moved to a model focused on squeezing revenue from digital subscribers by prompting them with a paywall. But because the amount of information available through the internet is infinite, with supply vastly outstripping demand, and because most folks transitioned to getting the news from social media, the MSM were forced to find a new commodity to sell. They settled on polarization.

This industry transformation didn’t bring any financial gains until Donald Trump arrived on the scene. Immediately following his election, shrewd media executives realized that the amusement-type carnival coverage based on the what-if fairy tale they treated Trump’s campaign as all the way up to November 8, 2016 would no longer suffice. A new style of reporting was needed, one free of the traditional strictures of commercial journalism. Objectivity was quickly replaced with shrill, self-righteous advocacy and an “oppositional” stance.3

To keep numbers up and the money coming in, and to lure converts past the pesky paywall, the MSM had to successfully use what’s referred to in the PR world as “a call to action.” They settled on rhetoric specifically meant to incite fear and angst. At every possible occasion, Trump was portrayed as a demonic figure Extremely Dangerous to Our Democracy™, a morally compromised madman who might well tell Vladimir Putin national secrets for funsies on days that he got bored with Twitter, and whom no Good Person™ could possibly accept.4

Using Trump as an antagonist, outlets like the New York Times and Washington Post began soliciting subscriptions as support for a noble effort—the protection of democracy from “dying in darkness,” as the latter put it. In this way, subscriptions essentially served as donations to a cause, with ideological values and anti-Trump content the crux of the commercial offer. This slowly forced mainstream journalism to mutate into what’s essentially crowdfunded propaganda, replacing reporting with commenting.

Note the rarely acknowledged conflict of interest at play here vis-à-vis the MSM’s continued Trump sensationalism: They’re profiting off of that which they pretend to be against. They need to maintain frustration and instigate polarization to keep subscribers and donors scared, outraged, and engaged. It’s to their benefit for Trump and his populist movement to remain relevant, as the oppositional stance to Trumpism has been their most profitable raison d'être. Another four years of Trump in the White House (or at least another election with Trump as the Republican nominee) would be the best thing that could happen to them. It would be another boon. Keep this in mind as the 2024 election draws near.

Today, as polarizing agents within a new business model dependent on engagement and subscriptions, the MSM sells validation. This is because nowadays the subscription-as-membership quality of paying for the news, which is the business model of a desperate, dying industry, means that people aren’t interested in the news so much as they are the news as presented from a certain angle. The New York Times, for example, is basically just a notary at this point. Its imprimatur and the fact that people know the Times is going to convey the news from the right perspective, that of the Good Person™, is why the paper has managed to survive the industry’s most turbulent years. Even if they don’t realize it, the vast majority of subscribers are paying to support a cause—that of ensuring a specific worldview, a specific creedo, is proselytized to others.

Without the advertising-dictated necessity to appeal to the median American, the inherent liberal predisposition of the MSM is now unchecked by any financial imperative, and the practice of objectivity is fading into obsolescence. As a result, editors have stopped adhering to the filtering policies that once incorporated the idea of the public good into news selection. It’s the will and wish of the audience that sets the filters of agenda now, with editorial policy subject to the ideological diktat of readers’ collective patronage. The price is the loss of newsroom autonomy.

This has led to the development of “post-journalism”—essentially, commentary commodified and sold as the modern-day version of news but which is funded through subscriptions, which are in turn solicited as donations. This new form of journalism, which is borderline propaganda, sells not the news, not even the truth necessarily, but an ethos and agenda to like-minded people, an orthodoxy already known to the “enlightened” whose job is to inform everyone else; it identifies and exploits the ideological concerns and values of an audience, which is fed only self-affirming narratives that vindicate partisan loyalties.

This crowdfunded journalism scheme obviously requires a reason for subscribing—a trigger, if you will. The MSM is thus incentivized to amplify and dramatize issues whose coverage is most likely to be paid for. Only news and opinions which help to solicit financial support can pass editorial scrutiny. Reader irritation and frustration must be continuously stoked because the more agitated and concerned and energized people become, the more likely they are to “donate” with their attention and money. It’s therefore to the MSM’s benefit to exaggerate issues and induce public unrest and outrage, which is why the news agenda has become narrower and more repetitive as journalists focus on select partisan controversies.

Consider the Trump-Russia collusion story that dominated coverage for years, a textbook example of discourse concentration. Martin Gurri believes the New York Times alone published more than 3,000 articles on the topic, with virtually every report either implying or proclaiming culpability with breathless anticipation. It was obsessive. Hatred of Trump was quite literally superimposed on objective reality by the nation’s most prominent newspaper, which was even awarded the Pulitzer in 2018 for “deeply sourced, relentlessly reported coverage” of “Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election and its connections to the Trump campaign.”

And when the Mueller Report found the collusion story to be wholly devoid of content, there was no soul-searching, no sense that the Times had incurred a journalistic disaster. Nor has the Durham Report had any effect; there’s been no acknowledgement by “the paper of record” that it was awarded journalism’s highest honor for desperately chasing a hoax based on a politically concocted lie. And that’s because the whole sordid affair was a massive post-journalistic success. At the beginning of Trump’s campaign, the Times had slightly over 1 million digital subscribers. By 2020, the paper reached a record-breaking 7 million—the first time the publisher brought in more revenue from online readers than its print subscribers. Millions of people had crossed into the paywalled haven to be reassured of Trump’s guilt and the imminent coming of the Trumpian End Times.

As the Russiagate surge in subscriptions and reader-driven profit makes clear, the most triggering issues are political topics that have the highest response potential and which polarize the audience. Andrey Mir writes, “If ad-driven media manufactured consent, reader-driven media manufacture anger. If ad-driven media served consumerism, reader-driven media serve polarization.” This is because according to the rule of allocative control, the origin of money impacts the mechanisms of selection in agenda-setting. Content production controlled by ad money tends to be corrected toward more neutral and positive news; but content production determined by reader money (or traffic) favors disturbing content, including polarizing political issues. Much like how the pursuing of ad money made the media industry impartial and politically disengaged, the pursuing of reader revenue is pushing the industry toward the poles of the spectrum. The more passionate and hysterical the coverage, the better.

Given the magnitude of the shift in the media ecosystem and the fact that the industry is losing its ad revenue and news business to the internet, it’s reasonable to conclude that polarization is here to stay and will only intensify under worsening business conditions that require appealing to divisive issues. Ever-increasing levels of agitation must be attained or the public’s attention will wane. Going forward, depoliticized media will be at a significant disadvantage and ultimately cease to exist, while traditional journalistic standards of impartiality, accuracy, transparency, and accountability will continue to deteriorate.

Advertisers’ preference for avoiding complex and troublesome contexts in favor of contexts that stimulated consumption had a statistically significant impact on the media industry. Risk-averse advertising money drove the media industry, in general, towards being more lifestyle- and celebrity-focused and less politically involved.

Studies show that political polarization in the U.S. reached a low point in the 1950s and started skyrocketing in the late 2000s, clearly coinciding with the decline of the advertising model in the news media.

CNN’s Jim Acosta: “Neutrality for the sake of neutrality doesn’t really serve us in the age of Trump.”

As Jim Rutenberg of the New York Times put it, “If you’re a working journalist and you believe that Donald J. Trump is a demagogue playing to the nation’s worst racist and nationalistic tendencies, that he cozies up to anti-American dictators and that he would be dangerous with control of United States nuclear codes, how the heck are you supposed to cover him?” The NYT newsroom evidently decided that Trump couldn’t be safely covered, he had to be opposed.

Journalists have always been a parasite class, the kind of people who peep through blinds for a living or find someone at the worst moment of their lives and stick a microphone in their face—"Your whole family has been murdered, how do you feel?"—and if you look into the run-ups to both WWI and WW2 you can find the most reckless cheerleading for bloodshed, committed of course by cowards who hid behind their desks while other men were massacred in droves.

I know we all have our pet peeves about the zeitgeist, especially those of us raised in 20th-century America still in shock over what's happened to the 4th estate, those supposed defenders of our sacred Democracy: journalists willing to lie with a straight face to protect the Narrative du jour ("no one teaches CRT, bigot!"), engage in the most scurrilous ad hominens against any dissenters ("must be on Putin's payroll!), brazenly lie about their political opponents (Don't Say Gay), attack other journalists for committing actual journalism, denounce half their fellow citizens as irredeemable bigots, and (maybe the worst crime of all): become vicious narrative-enforcement agents who attacked anyone who even quibbled with the Covid narrative ("our toddlers must be masked if it even saves one life, grandma killer!") while denouncing anyone as racist (!) who attempted to look into the origins of the virus.

(Really, it needs to be said again: imagine any other journalist or thinker from any other time in recorded history and tell them that there was a global pandemic but that EVERY establishment journalist in the country deemed investigating it a hate crime. IT BOGGLES THE MIND!)

But for me the grossest part of all this is the unwavering sanctimony these people have, how they imagine themselves moral avatars as if they're reincarnations of Mother Teresa, never not patting themselves on the back about how much they love the Marginalized and how much more virtuous they are than us benighted peasants.

An entire generation whose greatest moral conundrum is whether to swipe left or right imagines themselves a cross bw the French Resistance and the marchers on Selma because they don't hate black people and because they put pronouns in their bios!

Will no one rid us of these meddlesome priests!?

I always get the warm and fuzzies when I see something from Brad that's orthogonal to something I'm writing.........

The media's playbook consists of hatred and division. Advertising-as-revenue is a dead business plan, and it should be. Much better to be "beholden" to the readers -- who can drop your service at any time if they feel its not worth the money.