This is a post I wrote over a year ago. Back then I had maybe a few dozen subscribers. Now that I have many more, I thought I’d share it again. It’s a sprawling treatise, but I think there are some important takeaways about modern society that are worth contemplating.

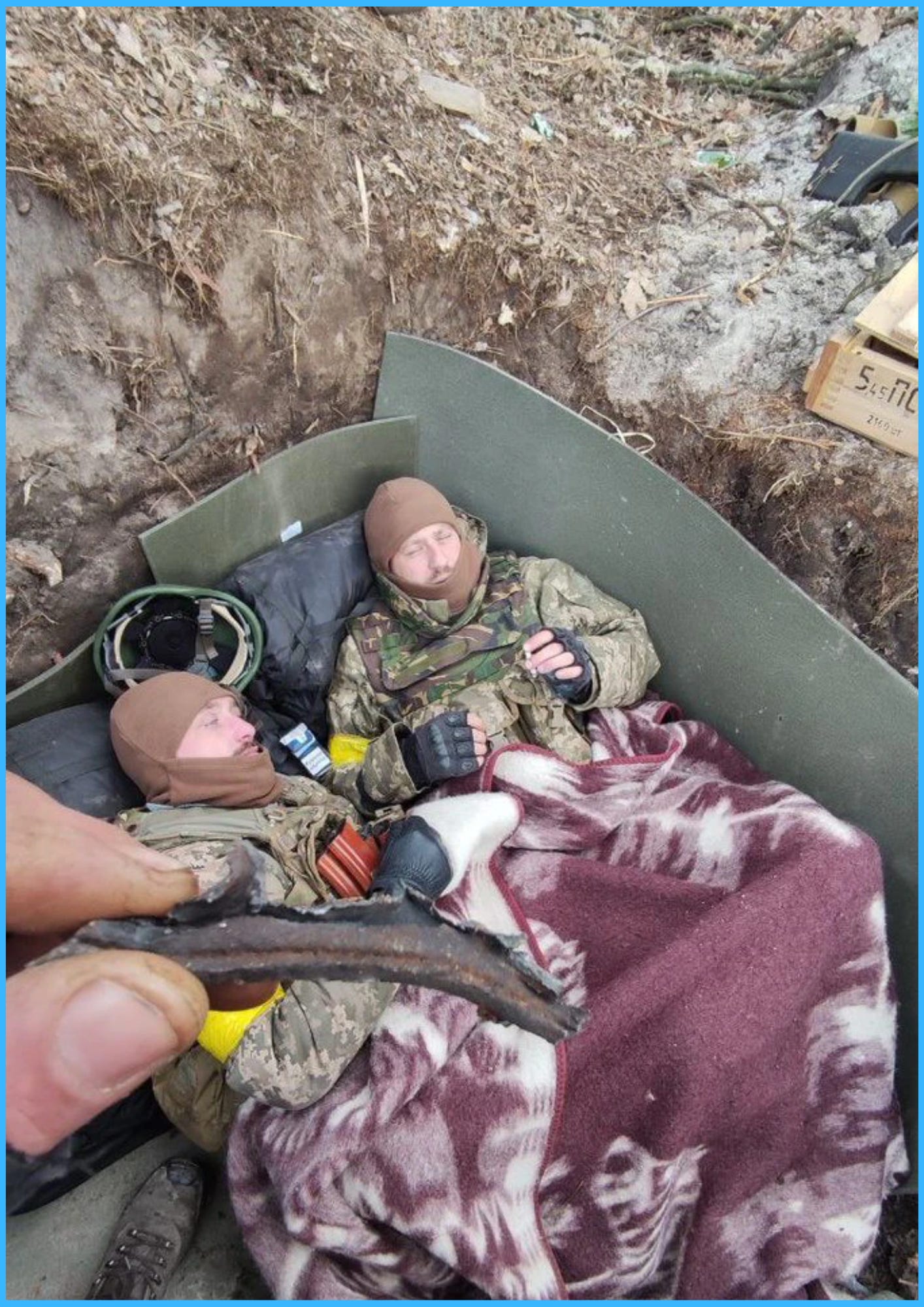

What if I told you that despite all the horrible, hellish things Ukrainians have been forced to endure at the hands of Russia’s genocidal aggression — the atrocities in Bucha, the destruction of entire cities that will take years and years to rebuild, the brutal austerity and deprivation that comes with living without running water and electricity and food and every other resource and amenity and luxury and creature comfort we so cavalierly take for granted, the capriciousness of fate amplified tenfold, losing loved ones, and countless other daunting experiences and compromises and forfeitures — what if I told you that many Ukrainians will miss “it” when it’s all over, that they’ll look back on this period with genuine nostalgia?

I’m not being facetious. Hear me out.

There’s a chapter in the novel I wrote, Because of Jenny, that was particularly difficult to “figure out.” It’s written in the second person and culminates with Jenny, one of the two main characters, being raped by her scumbag “boyfriend.” It’s not based on personal experience, obviously, but on the experience of someone I loved very much, and I also did a fair amount of research and reading in an effort to do right by those in the real world, the human beings off the page who have to count themselves among the victims of rape.

But you neither need to be a victim nor overly-familiar with rape to know it’s a deeply psychologically scarring event, certainly among the most traumatic experiences one might be subjected to. Recent studies indicate that 94% of rape victims experience symptoms of PTSD almost immediately following the attack, a number that drops to about 30% after nine months. That’s a significant drop, and pretty extraordinary when you think about it, especially compared to the recovery rate documented in Global War on Terrorism veterans. According to one study, PTSD among this group decreased from 28.8% at 1 month to 17% at 12 months.

PTSD can be a fickle affliction. At least, that’s what medical experts say. But there’s no question that the past few decades have witnessed an influx in studies with “paradoxical” findings. Take American soldiers, for example. You’d imagine there’d be a distinct correlation between combat veterans struggling with PTSD and suicide rates, but not so. Combat veterans are not significantly more likely to commit suicide than non-combat veterans.

This discrepancy isn’t unique to the American military. As Sebastian Junger points out in his book, Tribe, rear-base support personnel during the 1973 Yom Kippur War had psychological breakdowns at 3x the rate of frontline troops. A similarly puzzling deviation was borne out in a 1996 study on Gulf-War era military personnel: More than 80% of psychiatric casualties in the U.S. Army’s VII Corps came from support units that took almost no incoming fire during the air campaign of the first Gulf War. Even more surprising, American airborne units had some of the lowest psychiatric casualty rates in the entire military during WWII. That is extraordinary.

But it gets odder still.

Over the years, American casualty rates in each of the wars we’ve fought have dropped precipitously, and yet the number of PTSD and mental health disability claims has been inversely proportional. That is, in each conflict (i.e. - Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi freedom), despite casualties dropping relative to previous wars, disability claims have increased. The Vietnam War mortality rate was 25% of what it was during WWII, but Vietnam veterans filed for compensation at a rate 50% higher; the mortality rate in Iraq and Afghanistan was 33% of what it was during Vietnam, but there’ve been 3x as many PTSD disability claims.1

Correlation does not imply causation, and there are manifold reasons that might explain some of these modern irregularities. Perhaps stigma has improved and veterans have gradually felt more comfortable seeking help. Or, it could be a VA-related thing; maybe healthcare workers nowadays are more “accommodating,” or the government more willing to grant self-reported claims; or maybe it’s due to veterans “gaming” the system and taking advantage of permissive regulations. It certainly goes without saying that there are doctors who doubt the veracity of certain claims, though I kind of feel like that’s inevitable.

Understanding recent changes in how doctors analyze PTSD helps to sharpen the picture a bit more. Generally speaking, when we hear Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, we think of trauma, since, you know, it’s in the name, but apparently it’s more complicated than this.

Not only is trauma insufficient to trigger PTSD symptoms, it is also not necessary. Although by definition clinicians cannot diagnose PTSD in the absence of trauma, recent work suggests that the disorder’s telltale symptom pattern can emerge from stressors that do not involve bodily peril… significant PTSD symptoms can follow emotional upheavals resulting from divorce, significant employment difficulties or loss of a close friendship… students who had experienced nontraumatic [sic] stressors, such as serious illness in a loved one, divorce of their parents, relationship problems or imprisonment of someone close to them, reported even higher rates of PTSD symptoms than did students who had lived through bona fide trauma. Taken together, these findings call into question the long-standing belief that these symptoms are tied only to physical threat. — Scientific American

Per Sebastian Junger, only 10% of American military personnel experienced actual combat operations during GWOT, but the majority of those on PTSD disability include Navy and Air Force personnel who were nowhere near combat, as well as veterans who never deployed. Which means either a non-trivial number of veterans are indeed scamming the system, or the majority of veterans struggling with PTSD were affected by something other than combat operations.

While you let this marinate, note that while there’s no sure way of knowing what exactly explains all the aforementioned perversities (a quantitative approach only gets you so far, and any qualitative analysis requires a lot of deductive reasoning to arrive, with some confidence, at a conclusion), from a macro perspective there are some patterns that help formalize an observation, particularly in light of the fact that these patterns aren’t unique to PTSD in veterans.

To wit: It’s more or less common knowledge in the Peace Corps that returning home to a modern country is often more difficult for members than their experience volunteering in a developing country. One study found that no less than 25% of Peace Corps volunteers reported experiencing significant depression upon returning home, but this figure more than doubled among volunteers whose experience occurred in a host country either in a state of war, or grappling with a catastrophe or disaster. In other words, people find it more difficult to come home to the U.S. after volunteering in areas of the world where war and deprivation are the norm.

This is essentially akin to a young adult American woman from, say, nice and safe suburban New York, someone who grew up wealthy and relatively privileged and has access to all the benefits of living in the great US of A, coming home after a year in civil war-torn South Sudan — one of the most dangerous places in the world for aid workers, where few have electricity and food is scarce and folks live in thatched houses — and rapidly lapsing into prolonged depression with PTSD-like symptoms such as feeling detached from family and friends, feeling emotionally numb, irritability and angry outbursts, difficulty maintaining close relationships, concentration issues, etc.

The Curious Case of the White Indians

I finished reading this book a while back. Very much worth the read, probably a top 10 favorite of mine, and that’s saying something. There are a few pretty crazy anecdotes detailed within that provide some serious food for thought as far as human nature goes.

In 17th century colonial America, English monarchs specifically cited as a principal motive for colonization “settling the infidel’s world” the propagation of Christianity among the native peoples, who, although admittedly possessing rich and viable religious traditions of their own, were believed to be lost in the grips of Satan himself. Ergo, invariably, royal charters sanctioning settlement of the colonies declared that “the redemption of the savage soul” and “the conversion of the heathen” were of the utmost importance, and that settlers operate accordingly. Read: “Maketh contact with the savages and saveth them from their h’resy!”

This didn’t go over all that well. Turns out savages that don’t feel like they need saving don’t want strange white dudes in frilly outfits and tight pants carrying big sticks that shoot fire to try saving them, and that advocating for what sounds like insanity to people whose cruelty and capacity for violence had no precedence in the annals of planet Earth and who’d really just rather be left the fuck alone thank you very much does not jibe—especially if you don’t traffic in the truth very often, which the early white man was notorious for.

Not only did they inflict horrific suffering, but from all evidence they enjoyed it. This was perhaps the worst part, and certainly the most frightening part. Making people scream in pain was interesting and rewarding for them, just as it is interesting and rewarding for young boys in modern-day America to torture frogs or pull the legs off grasshoppers. Boys presumably grow out of that; for Indians, it was an important part of their adult culture and one they accepted without challenge. — S.C. Gwynne, Empire of the Summer Moon

Long story short, the colonists had about the same amount of success converting Native Americans to Christianity as I’ve had in my attempts to domesticate a raccoon. The Indians, like raccoons, didn’t assimilate all that quickly and revealed themselves to be sneaky little bastards more than capable of outsmarting their subjugators, and they kept getting away and running back to their own kin. A decidedly dispiriting affair, indeed.

And then in a not so surprising turn of events, the Native Americans demonstrated that they had zero reservations about coming back to snag some colonists the same way that the colonists had snagged them, except they’d kill the colonists in rather unpleasant ways, as you can imagine. They often saved the women and children, though, on account of deeming them worthy of assimilation.

Strange things started happening in the colonies. In 18th-century America, colonial society and Native American society sat side by side. The former was civilized and commercial; the latter was communal and tribal. As time went on, a certain trend manifested: No Indians were defecting to join colonial society, but many whites were defecting to live with Native Americans. And I’m not talking about going on a few hunting parties or trading some sparkly beads for buffalo hide or taking a weekend break from colonial life or something; I mean they actually said peace-out cub scouts and dove full-bore into the lifestyle of the so-called savage and quite literally became one.

Not only this, but colonists who’d been captured (and spared) by the savages ended up wanting to stay with their captors even when presented with the opportunity to return to their families, while the exact opposite behavior was still true of captured Indians—they wanted nothing to do with Western society and skedaddled as soon as the opportunity presented itself.

Benjamin Franklin observed the phenomenon in 1753, when he wrote:

Make no mistake about it, the difference between life as an American Indian and life as an American colonist was night and day. Even so, there were many documented incidents in which the following scene played out in some fashion: A mother and father desperately hoping to find their daughter, taken captive as an 8 year-old during a Comanche raid, spending the next however many months or years doing everything within their means to get her back, only to be stupefied when, after she’s finally discovered, she refuses to come home. Sometimes the Native Americans could be persuaded to trade (sell) the individual in question, only for the “rescued” to abandon their rescue party ASAP and return to the savage folks.

By all accounts there was some kind of mysterious appeal to the Native Americans, some irreconcilable differences between the two societies. Here’s what one captive-turned-white-Indian, eight year-old John McCullough, said about the “rigorous program of physical training” his adoptive Indian uncle put him through:

“In the beginning of winter, he used to raise me by day light every morning, and make me sit down in the creek up to my chin in the cold water in order to make me hardy as he said, whilst he would sit on the bank smoaking [sic] his pipe until he thought I had been long enough in the water, he would then bid me to dive. After I came out of the water he would order me not to go near the fire until I would be dry. I was kept at that till the water was frozen over, he would then break the ice for me and send me in as before.” As shocking as it may have been to his system, such treatment did nothing to turn him against Indian life. Indeed, he was transparently proud that he had borne up under the strenuous regiment “with the firmness of an Indian.”

As the historian James Axtell wrote, “In public office as in every sphere of Indian life, the English captives found that the color of their skin was unimportant; only their talent and inclination of heart mattered.”

Reading this, I was reminded of a speech that President Teddy Roosevelt once gave at my alma mater:

Of all the institutions in this country, none is more absolutely American; none, in the proper sense of the word, more absolutely democratic than this. Here we care nothing for the boy’s birthplace, nor his creed, nor his social standing; here we care nothing save for his worth as he is able to show it. Here you represent, with almost mathematical exactness, all the country geographically. You are drawn from every walk of life by a method of choice made to insure, and which in the great majority of cases does insure, that heed shall be paid to nothing save the boy’s aptitude for the profession into which he seeks entrance. Here you come together as representatives of America in a higher and more peculiar sense than can possibly be true of any other institution in the land. — President Theodore Roosevelt, at the West Point centennial, 1902

Today, American Indians, proportionally, provide more soldiers to America’s wars than any other demographic group in the country.

The Sacred Band of Thebes

In Plato’s philosophical dialog, the Symposium, a group of Athenian aristocrats sits at a banquet discussing one of the more popular topics of conversation in ancient Greece: Eros, or love.

One of the guests, Phaedrus, waxes lyrical about the loyalty that the lover has to his beloved. He speculates on the bravery that such soldiers might exhibit on the battlefield:

If by some contrivance a city, or an army, of lovers and their young loves could come into being . . . then, fighting alongside one another, such men, though few in number, could defeat practically all humankind. For a man in love would rather have anyone other than his lover see him leave his place in the line or toss away his weapons, and often would rather die on behalf of the one he loves. — The Symposium

In ancient Greece, homosexuality was an accepted part of life. In fact, homosexual couples often exhibited such devotion to each other that Plato decided to actually propose the formation of an army unit composed entirely of gay couples, the rationale being that lovers would fight more fiercely and cohesively than strangers with no ardent bonds. It wasn’t a stunt. Circa 378 BCE, such a unit was formed in the Theban army, an elite fighting division called the Sacred Band of Thebes that consisted of 150 pairs of gay lovers.

And they were straight up badasses. So much so that the Theban general Pelopidas formed these couples into a distinct unit – the “special forces” of Greek soldiery – and the forty years of their known existence (378–338 BC) marked the pre-eminence of Thebes as a military and political power in late-classical Greece.

The Sacred Band fought the Spartans at Tegyra in 375 BC, vanquishing an army that was at least 3x its size. It was also responsible for the victory at Leuctra in 371 BC that established Theban independence from Spartan rule and laid the groundwork for the expansion of Theban power. Their only defeat came at the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC), against Philip II of Macedon and his son, Alexander the Great. The Sacred Band was surrounded and given the opportunity to surrender, but just as Plato predicted, the lovers chose instead to fight to the end.

All 300 soldiers of the Sacred Band of Thebes were slaughtered. But their reputation was such that Philip II reportedly wept at the once-mighty army of male lovers reduced to a pile of massacred bodies. Buried on the battlefield where they fell, they were found in 1880. In discovery, the most notable feature of the skeletons was their arrangement: They were in rows of seven or eight, mimicking the formation of a phalanx. Some of the pairs of corpses had arms linked together at the elbow, indicating they’d died that way.

“Chronic neurotics of peacetime now drive ambulances.”

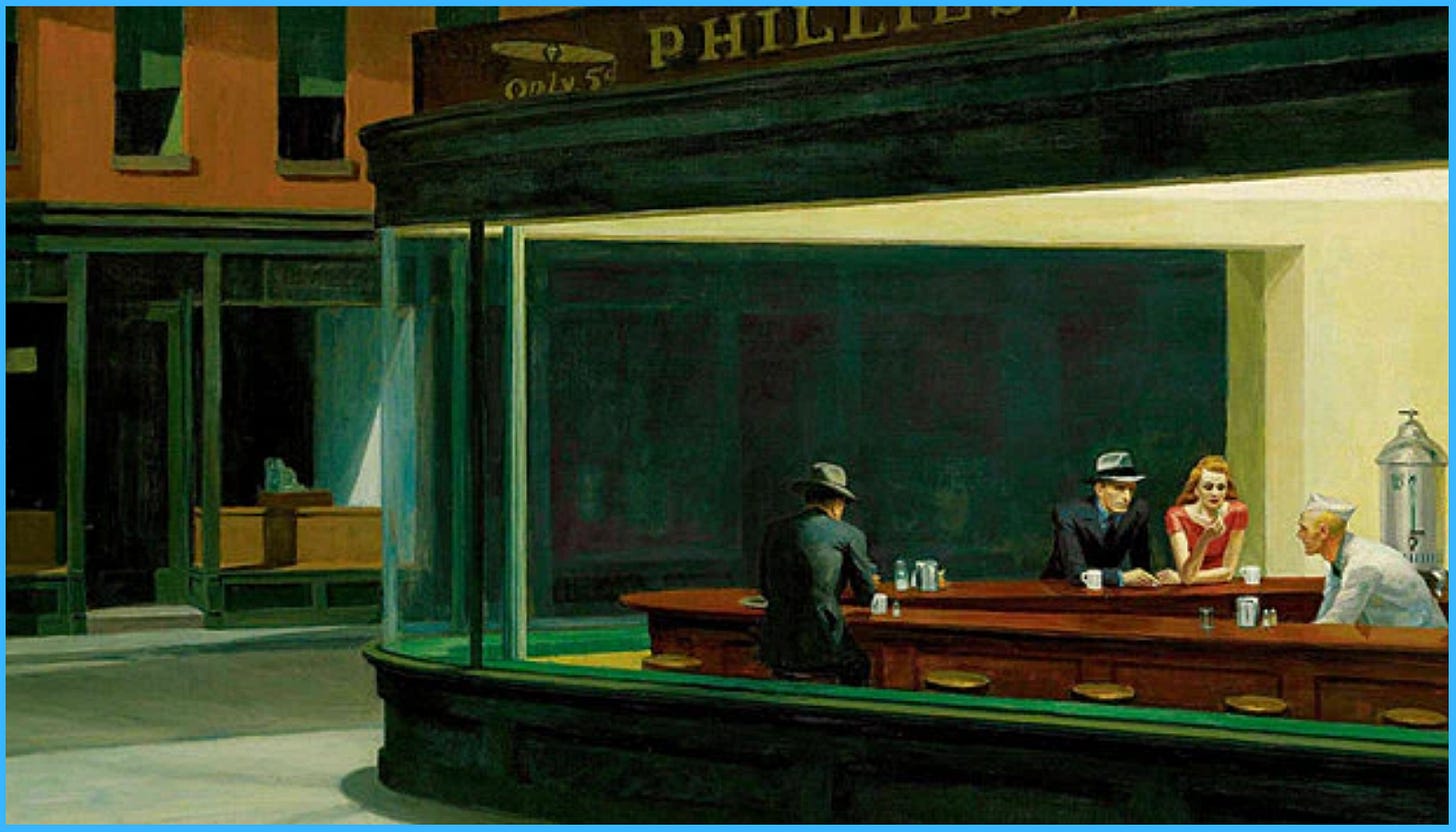

The London Blitz is a fitting example of how social cohesion and comradery can be psychologically protective.

Prior to the start of World War II, British planners took to estimating the effects that a German bombing campaign would have on England. The prognosis was a bit short on optimism. In The Splendid and the Vile (highly recommended), Erik Larson quotes one military planner: “London for several days will be one vast raving bedlam. The hospitals will be stormed, traffic will cease, the homeless will shriek for help, the city will be a pandemonium.”

Well, Hitler did indeed bomb the hell out of London for 57 consecutive nights, the idea being that, were Germany to succeed in breaking British morale, British civilians would pressure the government into surrendering.2 Some 43,000 people were killed and at least 1 million homes destroyed, but the dire predictions from British planners couldn’t have been more wrong.

The London Blitz turned out to be a massive strategic mistake for the Germans. Rather than break morale, Hitler just really pissed everyone off and anchored collective resolve to see the war through.

To say that British civilians proved remarkably resilient during the Blitz would be an understatement. Psychiatric hospitals around the country saw admissions go down. Psychiatrists even watched in puzzlement as long-standing patients saw their symptoms subside during the period of intense air raids. Even epileptics reported having fewer seizures. “Chronic neurotics of peacetime now drive ambulances,” one doctor remarked. Another ventured to suggest that some people actually did better during wartime.

During the war, the British government ran a project called “Mass-Observation.” Comprised mostly of volunteers, their job was to record and study how civilians responded to the wartime hardships. Kind of like scientific people watching.

Government censors found that morale was actually highest in the most badly hit places. When you read through diaries and letters from during the Blitz, you do come across some passages that describe raw terror—but mostly they are filled with descriptions of surreal circumstances, rendered in a quotidian, unemotional, and matter-of-fact tone.

People felt they were achieving moral victory merely by staying alive. “Finding we can take it is a great relief to most of us,” one woman wrote. “I think that each one of us was secretly afraid that he wouldn’t be able to, that he would rush shrieking to shelter, that his nerve would give, that he would in some way collapse, so that this has been a pleasant surprise.” A man wrote, “I would not be anywhere in the world but here, for a fortune.” — David Brooks, The Atlantic

What’s ironic is that government officials weren’t all that happy about the Mass Observation findings. Why? Because it sort of undermined their own cause when, later in the war, the Allies decided to do to Germany what Hitler had done to the British—bomb civilians with the specific goal of terrorizing the population and forcing a surrender. Only, what they did to Germany was incomparably worse. Even today, a lot of people aren’t aware of this because it’s a controversial bit of history that tends to be whitewashed, but less than a month after we lost roughly 19,000 soldiers in Germany’s Battle of the Bulge offensive and just three weeks after we discovered Auschwitz, the American and British air forces conducted a joint, 3-day fire-bombing operation on the city of Dresden, a key industrial cog of the German war machine, and it was bad. The incendiaries created a firestorm with such powerful winds that all the oxygen was sucked out of the air. Clean-up efforts reportedly found shelters and basements full of people who looked like they’d all experienced heart attacks simultaneously. Mass asphyxiation.

More people were killed in Dresden the first night of the Allied air op than London lost during the entire war. Estimates vary, but it’s believed upwards of 1 million were killed/wounded over the course of just 72 hours.

American analysts based in England monitored the civilian population to get a sense of Dresden’s impact on German morale, only to discover that they (the Allies), too, had achieved the opposite of what they’d hoped: the German population became more defiant. In fact, the cities with the highest morale were the ones, like Dresden, bombed most heavily. According to German psychologists who compared notes with their American counterparts after the war, it was the untouched cities where civilian morale suffered the most. Thirty years later, a dude named H.A. Lyons analyzed the same phenomenon in Belfast.

Charles Fritz was a captain in the U.S. Air Force assigned to study the impact of strategic bombing on Germany. Curious that overall population resilience notably increased in response to bombings, he went on to study how communities responded to natural disasters. Fritz was unable to find a single instance where communities hit by catastrophic events lapsed into sustained panic, much less anything approaching anarchy. Indeed, he found that social bonds were reinforced during disasters, and that people overwhelmingly devoted their energies toward the good of the community rather than just themselves.

Fractured

It is not a divine epistemological mystery as to why, on a per-capita basis, the U.S. is the worldwide leader in mental health issues. Our consumerist country is alienating and cold. The individual reigns supreme. It’s not so much survival of the fittest as it is every man for himself, and when you add in self-appointed cultural gatekeepers who, in pursuit of profit and power, intentionally sow discord and strain the tenuous threads keeping our social fabric intact, and then you toss in the identity politics commissars who seem to genuinely relish taking a hammer to our anemic, cracked façade so that the country breaks apart along every demographic fault line possible, you get modern America in all its repulsiveness, which is completely antithetical to life in the military.

A lack of social support has been found to be twice as reliable at predicting PTSD symptoms than the severity of trauma, which is to say that if enough people of whom your society is largely comprised have normalized a culture of self-interest and me-first bullshit, reintegration is infinitely more difficult; mental health issues and other PTSD-like symptoms are exacerbated, and poisonous ameliorators become increasingly tempting. The disparity is severe enough to effectively leave someone existentially adrift in a sea of loneliness, treading water with bricks glued to their feet and no sign of land in sight, doing as best as possible to keep their head above water.

Our country is fractured. Deeply, deeply fractured. The reasons are many, as are the culprits, but in my opinion the one entity largely responsible for our atomization is the mainstream media. Its business model is dependent on monetizing division, meaning there’s a greater incentive to light fires than put them out, and they therefore serve up an infinite menu of cultural flash points and battlefields on which to wage war, inciting moral panics and witch hunts during intermissions.

But it’s not just the industrial media complex that’s to blame. We the people have been more than happy to oxygenate the conflagration in ways big and small, petty and profound; it’s we who’ve normalized the divisive antipathy permeating all levels of society.

This isn’t about one party; it’s not solely a left-wing or right-wing problem. If you’ve managed to hang on to any semblance of objectivity, you know that both sides of the political spectrum happily discard critical faculties when the political circumstances call for it, and that fidelity to the truth and other antiquated concepts like facts and reality and decency matter less than ideological considerations and reconciling reality to one’s online-derived informational bubble. While we see our own political opinions and motivations as nuanced and sophisticated, we look at the out-group, the people outside our tribe, as simple, one-dimensional caricatures unfit and unqualified to participate in public discourse.

The mutual acrimony and resentment sanctify the promotion of polarizing political content specifically curated to keep the citizenry enraged and atomized, and the carousel goes round and round while the actual baddies profit at our expense. Q.v. — The unprecedented upward transfer of wealth during the pandemic while a certain segment of our country obsessed about the need to implement vaccine apartheid, forcing the other segment of our country to focus on fending off the former.

It does not help that our media luminaries and influencer class and academic custodians and government officials are always so invested in the flavor-of-the-week drivel that’s like a fodder-ladened conveyor belt for partisan cat fights, the latest “issues” that have soft-bodied Blue Check Brigade-types squabbling like self-important sock puppets with an arrogance that’s normally just shy of that collectively exhibited by the co-hosts of The View — not the brightest bulbs in the luminary chandelier and dwelling always at the edge of some vast continent of hysteria so as to not leave open any chink in consciousness through which they might be waylaid by an awareness of how circumscribed by galactic reservoirs of ignorance their lives are, and yet somehow all still in possession of considerable social capital — and these issues, these disputes that have folks in full-scale existential conniptions, are undoubtedly viewed from afar by people in other countries with a mixture of disgust and clinical-like fascination, as they should be.

It’s embarrassing. When this is the norm in a given country, you know that country must be in some measure wanting. It pains me to watch America grow steadily more polarized and weak; to watch both sides of the political spectrum refuse to walk away from the game of mutual provocation and pseudo-outrage.

“God we need another war.”

What’s the solution, the antidote? I’m not sure. What I am sure of is that if you take a die-hard liberal from San Francisco, perhaps a white dude with soft palms from a wealthy background and the progeny of parents who happily bought him a BMW for his 16th birthday, a guy who thinks Trump is the antichrist and Joe Rogan is a Weapon of Mass Destruction and all conservatives are uncivilized brutes—if you take this very left-wing and not all that tolerant fella and you pair him up with, let’s say, a hardcore conservative from Atlanta, maybe a black dude with calloused palms from a single-parent home, a guy who’s never had a car before and thinks that Biden is a POS and it’s a crime against humanity that Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton hasn’t been locked up yet and all folks of the liberal persuasion are a scourge on America—if you take this very right-wing and far from broad-minded gent and pair him up with the aforementioned liberal, and you put these two antipodal dudes in a foxhole in sub-freezing temperatures for, say, a week, and you give them 7 MREs total between the two of them, and you make them do a bunch of hard, uncomfortable shit together every day only to return to that same foxhole in the evening to freeze their way through the night together, permitting sleep only between the hours of 0200-0600 as long as one of the two dudes is awake keeping watch while the other has his eyes closed — and you make this week-long suckfest a pass/fail exercise that determines whether they 1) get to see their families after 3 months away, or 2) have to recycle and start the exercise all over again— if you do this, I know beyond a shadow of a doubt that, at a minimum, it’ll end up being a therapeutic and liberating experience to be drawn outside themselves and into the world of someone it’s unlikely they’d ever cross paths with otherwise, potentially forever changing such time as remains to them on earth, affecting how they henceforth see their fellow Americans and the big wide world.

Sometimes, when exasperated by the latest culture war meltdown, I’ll think “God, we need another war.” Not because I want the people I’m annoyed with to die, or for the soft and coddled to suffer. I say it with the benefits of war in mind. Which I’m not suggesting outweigh or even neutralize the terribleness of war, but which exist nonetheless.

Contemporary technology and the genius of invention have never been so prolific as now in devising the implements of war and improving man’s ability to kill one another, and yet, even so, war does not appear to harden societies.

In fact, over the last 15 years or so there’ve been 19 different studies in over 40 countries that have fought wars — even the most brutal of civil wars, like that of Sierra Leone, which saw widespread mutilation and massacres — and each study has revealed the same thing: Exposure to wartime conflict, training, destruction, violence, deprivation, suffering, etc., fosters society-wide altruism to such a remarkable degree that post-conflict countries seem to experience near-miraculous economic and social recoveries.

Historians and anthropologists alike have long noted the “positive” changes that occur in societies during and in the wake of wars, but only relatively recently have interdisciplinary teams of researchers — in economics, anthropology, political science, and psychology – conducted studies to understand specifically why wars have, in example after example, ushered in tangible social progress in the form of everything from increased community participation and generosity and pro-social values to the implementation of egalitarian social policies. What’s more, these studies illustrate how subsequent progress withstands the test of time, instilling markedly improved levels of trust, cooperation, benevolence, and forgiveness among people. Far from being ephemeral, the positive changes are still tangible decades later.

Proximity Breeds Closeness

I’m obviously not suggesting we use war to change America for the better. But the underlying mechanisms by which war seems to improve a society are worth exploring. I don’t want another war; what I want is the cohesive effect that war and national purpose and shared adversity engender. This goes back to the “What’s the solution?” brain buster. I kind of already answered it. I mean, I’m not saying it’s “the solution,” a panacea, but it would definitely help.

Put plainly: Make dissimilar people do hard shit together. Even more bluntly: Make dissimilar people do hard shit and also suffer together.3 I’m not advocating for widespread sadism. I’m talking about shared adversity — and I mean real adversity, not a rainy day in Los Angeles — that would require folks to, among other things, live more fully in an atemporal present, freed from the burdens of consumerism, and get closer than their phone screens. Proximity breeds closeness.

During periods of extreme challenge and adversity — like, for example, the war in Ukraine — social priorities are radically divergent from what normal life calls for, so much so that it can lead to people abandoning the petty minutiae and politics and indulgences that would otherwise hold them back from casting aside prejudice. Under the right circumstances and conditions, you can erase differences in class, race, sex, background, education and so on and so forth by making people blind to those differences.

Dare I say it, progressives would chill out with the “Not using my preferred pronouns is violence!!!” type of stuff if they had to figure out how to get some fresh water after a 500 pound Russian FAB broke the water main; and they might very well never again dilute the meaning of the word “violence,” as a bonus. And the pasty racist down the hall would probably forget his black neighbor’s skin color, or at least stop being such a racist asshole, if that pasty racist’s wife of ample flesh and proportion were bleeding out and needed to be carried to the aid station and there were no wheelbarrow in sight, and the black neighbor sprang into action without thinking twice about it and helped save her life.

But it doesn’t even have to be some kind of existential crisis. Exercises in solidarity fundamentally reject the primacy of self-interest at the expense of the greater good. These are times when people must depend on one another in ways that promote humaneness and existential clarity, the latter of which I think of as an acute, abiding understanding of what’s most important in life and why. And, just like during the London Blitz, the intense comradery facilitated by this change in priorities is powerful enough to stir up nostalgia. It’s primal; it leads to emotions and insights and revelations that simply cannot be experienced under other circumstances, and it dilutes contemporary life of all its deafening bullshit so you can actually cut through the Gordian knot of abstractions.

The moment you can get the spaz liberal and the raging conservative to see their mutual interests have more in common than they have in conflict, and that what makes them similar dwarfs what makes them different, that’s the moment progress starts. The problem is that it’s becoming increasingly difficult just to get people to open their front doors and venture outside and interact with strangers. It does not portend well when many of us exist online more than we do in real life.

This digitization was already happening prior to the pandemic, and it appears that our futile covid mitigation efforts really did a number on some individuals. That’s not good, nation. Interaction between people can’t only be online or at a distance, yet it seems this is rapidly becoming the new norm. Our tenuous national adhesive won’t last, not when nowadays the standard way of dealing with anyone we don’t consider part of our tribe — which basically means everyone we’re unfamiliar with or who’s “different,” so approximately 8 billion people — is to reduce the person in question to crude stereotypical characteristics that lead to simplistic generalizations. And rarely are we correct in our assumptions.

But radical changes in place and context and circumstances have a salutary effect. We are most affected, and most influenced, by experiences. Humans are hardwired to crave for, and thrive in, situations when comradery and group dynamics are organic. Sure, it’s not necessarily going to facilitate the kind of momentous occurrence capable of shifting the tectonic plates inside your head, but chances are, it’ll be like a balm for the soul. If only we could bottle that feeling, that elixir, and sell it.

I couldn’t find anything on where the U.S. ranks relative to other countries in prevalence of PTSD among soldiers, but American soldiers suffer PTSD at around 2x the rate of British soldiers who served beside them.

Putin tried the exact same strategy in Ukraine.

Mandatory military service would do the trick. If every young American were required to serve in the military for just a couple of years, I believe it would have a profoundly beneficial and long-lasting impact on the country.

At 21 years-of-age I "went as a pilgrim" on a 3 month back-packing trip throughout India (December 1970 - February 1971), traveling by rail (third class) and sleeping in baggage racks. There was much poverty and suffering. However, there was also a strong sense of community and acceptance that "this is the life I've been dealt" and I will struggle however I must to survive, and find joy in whatever pleasures I can. Most people seemed genuinely happy, friendly and welcoming. The core of their happiness seemed, to me, to be rooted in family and community, and that they were all in the same circumstance. In poverty they still had meaning and purpose.

Your sombre article looks through some windows at lives that, while lived in-extremis, provided authentic meaning and purpose. And through other lenses at human behaviour in circumstances many of us might not volunteer for. Or at life through the lenses of those ill-fated and cruel'ed by crime and trauma. Tragedy is often all around us, even if we don't see it. But so are nature and beauty and kindness and community, if we're able to embrace it. Unfortunately, modern western life seems more focussed on division and conflict. A sad and dangerous state of affairs.

Thanks for your considered articles Brad, always a pleasure to read.

Well done and interesting article.

In the beginning, it seemed like the COVID pandemic would be the disaster that could remind us all of our common humanity. “We’re all in this together” we were told. Until it turned out that some of us were not only above the fray, but actually benefitted from it. And used that position to grab power and control over the rest of us.

It seems even disasters and tragedies cannot bring us together, unless we share common values to start with. When some have the goal of domination over the entire group, the old saying “don’t let a good crisis go to waste” comes to the fore. That’s what we saw with COVID. The crisis passed, and we are more fractured than ever.

Maybe the next crisis can cause a true examination of the consequences of really bad ideas.