I went to the meeting...

...The one the woman at Amor-Vincit told me about.

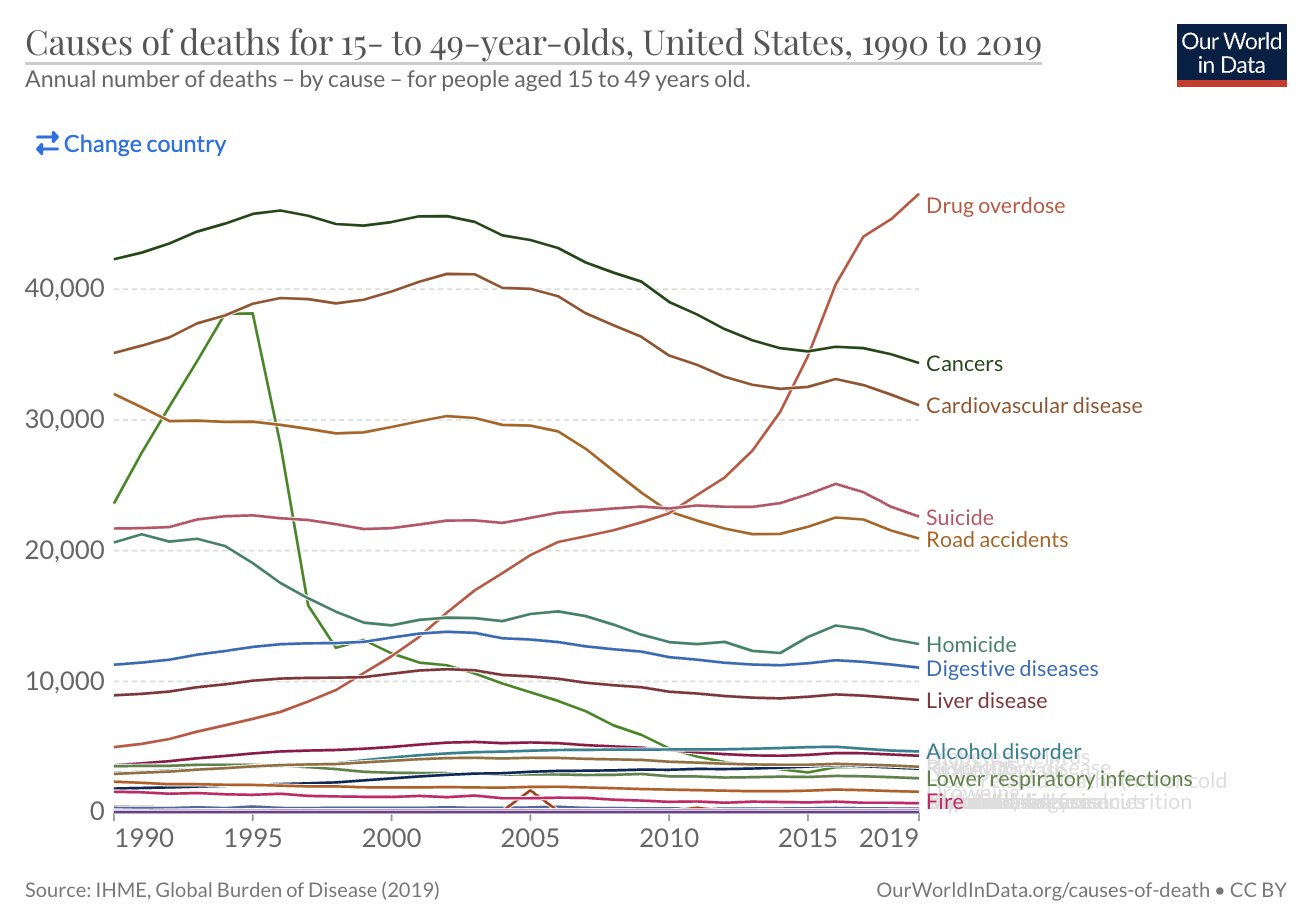

I was early, so I plopped down on one of the couches in the lobby and flipped through some brochures on the opioid epidemic. I spent the next five minutes trying to wrap my head around two of the facts listed on the first page: Drug overdoses were now the top cause of death for individuals ages 15 to 49 in the United States; and nearly 107,000 Americans died of drug overdoses last year.

I felt guilty for not giving much thought to the issue prior to meeting Jenny; before then, the extent of my knowledge was what little information I inadvertently picked up secondhand. Meeting Jenny had obviously spiked my interest, and while she was detoxing I started looking into things on my own. I was vaguely aware of the magnitude of the problem and how quickly the scourge of heroin had metastasized across the country. That was about it, really. But as more and more stories began filling up the local newspapers, the standard preconceptions that most people shared (including me) were repeatedly proven wrong. The opioid epidemic didn’t discriminate; it cut across all classes, affecting people from all walks of life — not just street junkies — and the severity of the issue was such that it was becoming increasingly difficult to find someone who hadn’t been impacted in some way.

As a kid growing up, the common perception of a drug addict was someone who willingly chose to endure the hardships brought on by substance abuse. I was led to believe that these people had chosen to live on the periphery of society, and that their continued drug use was because they either didn’t want to get clean or they simply didn’t try hard enough. It was only after I had met Jenny, when I took the time to listen and dig into the issue myself, that I realized this was not an accurate assessment of people struggling with drug addiction, nor was it particularly fair. Not only did it ignore the highly complex personal reasons why someone might turn to drugs, it also completely glossed over the ways in which a person might be congenitally predisposed to resorting to substance abuse in the first place.

This mischaracterization wasn’t all that surprising to me. We tend to project evil intentions onto any behavior we don’t understand. Our selective exposure to certain types of people — people we feel comfortable with — severely limits our ability to understand those who are different from us, particularly those who struggle with issues and problems that we don’t relate to. Which means that even though addiction might be a concept that’s a complete mystery to us, there has never been much incentive to change this. Perspective matters.

The meeting was held in the basement of the main Amor-Vincit building, a location which I was apparently alone in finding chilling in its underground, dank atmosphere. To get to the room we had to follow a long adit-like tunnel with halogen lighting and white cinder-block walls — the sort of creepy walls that are cold to the touch and oddly textured with globs of old paint — and for some reason we walked in a single file line despite having no need to, like we were all being led to the gallows.

The actual meeting room was windowless with yellowish walls, and the floor was tiled with the same kind of tile you always see in older classrooms, the pasty white squares flecked with strange flakes of blue and brown and streaked with black scuff marks randomly here and there. In the middle of the room was a circle of brown, metallic folding chairs.

I found an open seat and sat down. Even with the room full of people there was a palpable hush, the silence akin to reverence; you’d have thought we were about to take part in a cult ritual or something. Polite nods were exchanged between attendees like funereal, obligatory acknowledgements. It was soon abundantly clear that I was everyone’s junior by a considerable margin. If I had to guess, I’d say the majority of those joining me in the circle were in their late 40’s to early 50’s, with more women than men, and a lot of gray hair, a lot of faces etched with wrinkles and lines, and a lot of sadness, which you could not only see, but feel.

“Well everyone, hello and welcome back, and hello and welcome to our new faces today,” a plump woman with eyes too big for her face said. She had brown hair with strands of blonde, and the way she smiled seemed completely out of place given the circumstances. She wore a dark blue sweatshirt with a sticker name tag that read Rachel, along with a baggy pair of dark blue sweatpants, an outfit which in its sum made her look like a big blueberry but was also vaguely reminiscent of a prison uniform.

“I hope everyone is doing well and that things have been okay since our last meeting,” Rachel said, slowly looking around the room. A few people nodded back solemnly. Her jovial mannerisms clashed with the room’s vibe. This was a place where you felt guilty being cheerful. “Now, before we begin, just to reiterate, this is a closed meeting, but an open discussion. And that means everyone is welcome to share and to talk, but let’s try to keep it at a two-minute maximum, please. That way everyone has a chance to speak if they’d like to. Remember that nothing said here is to be repeated outside of this circle. We respect the privacy and boundaries of all those present, and we do not pass judgment or condemn or raise our voices. So, who would like to begin today?”

An uneasy pause followed. People adjusted themselves, switching crossed legs, straightening up, gently pulling purses to laps.

“I’ll go.”

A small woman on the opposite side of the room tentatively lifted a hand without removing her eyes from the floor. She wore a gray cardigan and faded blue jeans, and her hair was prematurely graying. A thin gold necklace ran across the bridge of her neck, a small gold cross visible just above the top button of her shirt. She sat up a little bit more and snuck a quick glance around the room and another at Rachel before crossing her arms and directing her eyes downward again.

“Thank you, Beth. Whenever you’re ready.”

A few heads perked up and turned toward Beth. After a pause she removed something from her pocket, cradling it in her hands. It looked like a small picture.

“Tomorrow makes four years since Tommy passed.” Her voice was shaky. She brushed a bit of hair over her ear, fidgeted with her hands. “It doesn’t seem possible, but somehow it is. It being four years, I mean. It feels like it was just yesterday. It really does. And I sometimes wish…I sometimes would rather it feel—that it really did feel like four years since, because I think if that’s how it was, if that was the way it seemed, then maybe it would help forget about it a little bit. And I know. I know. It makes me so disgusted with myself, knowing a part of me wants that, wishing time would speed up so the memory would soften or…I don’t know. Just get easier.”

It was now so quiet that even the slightest posture adjustment seemed deafening.

“I’m sorry, Tommy,” Beth said, and this time her voice had a catch in it, a kind of failure of breath, and it undid me. “I’m sorry I couldn’t save you. I’m sorry for what I said. I’m sorry.”

She was crying, weeping as only a mother who has lost a son can, with the kind of ineffable sadness that none but the sufferers themselves can fathom, a grief so difficult for the mind to cognize that it exceeds the human vernacular and makes any attempt to share comforting words seem empty and worthless and somehow juvenilely naïve. For the first time ever, it occurred to me how incredibly exhausting being a mother had to be given the enormous, fatiguing fragility of a child.

“At night I think about what Tommy’d be like today. If he’d still smile when nervous and like his pizza without the sauce and get super excited about fantasy baseball. I wonder what the Tommy of today would look like. What his family’d look like, his children. What his wife would be like. What kind of home they’d have. And I’m still so angry that nobody found him sooner. How can it be that nobody saw him, nobody went to check on him that whole time? Because my heart tells me he didn’t go right away. He was still there, he was still breathing for a long time but nobody was there to help him.”

Now I understood why so many faces were canted downward. I tried to be polite, looking up at Beth while she spoke. I wanted her to see that I was listening. But my mouth was dry and my eyes started to feel sandy and I was too uncomfortable to keep my gaze level any longer. I had to look down because I didn’t want anyone seeing me crying, but even though the meeting had just started it was like it was impossible not to cry. A tear began to tickle my cheek. And I wanted to get rid of that tickling sensation, I wanted to wipe away the tear because I wanted to hide that admission of weakness, but I knew that if I did, if I brought my hand up and cleaned up my face, then everyone would know for sure that I was crying, and I started wishing I was somewhere else, but then I remembered why I had even come in the first place and how this wasn’t about me, it was about Jenny.

A skinny guy sitting directly across from me raised his hand to speak next. Dressed in ragged, dark blue denim jeans and a t-shirt two sizes too big for him, he was sitting in the classic prep-school-slouch position with his chin resting on his hand and the bangs of his long, brown hair partially masking his right eye. Something oddly indefinable about him suggested a diet of coffee and cigarettes. He looked strangely confused, as if he wasn’t entirely sure where he was.

“I, um. I haven’t been doing too hot lately. Been doing bad, actually. I had two months clean and…I don’t know. I don’t know, you know? I don’t know what it is, but it’s like every time I get to that two months I just crack man, I just crack, and I don’t think twice about it. It’s like…it’s like I’m not even me, like, I’m not even in my body, it’s someone else and I can’t stop, I can’t figure out how to pump the brakes and just hold on and ride it out for once, you know? And it makes me hate myself. Because I know it’s ‘cause I’m weak.”

He paused, shaking his head, examining his hands.

“I just can’t stop. I used to be scared of dying. But now I don’t even care. I’ll do anything for the high. I’ll do whatever it takes, damn the consequences. And now I’m back to my old tricks. Working the corners. Nothing on my mind but getting money to score. What a surprise, right? What a fuckin’ surprise. I’ve been waiting for the old dudes to come by and I’ll offer them top for real cheap, like $20 a pop, money upfront, and as soon as I get it, I run like hell and I don’t ever look back. I just run and run. But I’m always thinking, I’m always feeling like it’s only a matter of time before I get what’s coming, you know? Like it’s only a matter of time before I get that bullet to the back of the head…I hate it. I hate it more than anything else in the world. I hate how I live now. Like, I spend every second of my life trying to get some money together for that next hit…and I never have enough for a wake-up shot, and even when I do and I try to save it and not do it before morning comes, I still end up doing it all anyway, I can’t hold off until waking up. I can’t even fucking fall asleep if I know it’s sitting there, waiting for me. I always just shoot up again. And then I wake up sick, you know? And then I have to go back out and do...do what I do to get money to score again. And it’s just this endless cycle man, it’s the same shit every day and the only thing different is the day of the week but you can’t even remember what fucking day it is because you’re so strung out all the time and you have no time to just stop and chill and live for a second, you know? And, I know it’s not worth it, it’s never been worth it, and this life is all struggle and no reward, the shots don’t even last long enough anymore and half the time you pick up that filtered down stuff those fuckers hock, that Black Tar they cut so they can pocket a piece of the take without anyone finding out…”

As the meeting went on I became more and more fascinated. It was amazing how simply listening to people in the circle talk — by listening to their stories — things began to make sense, and issues, problems and perspectives that were once completely abstract to me were suddenly understandable. Listening gave me an aperture into a world I had been clueless of. A lot of people talked about how difficult it was to get help for their kids. Sending them away to a specially purposed recovery program was known to be effective sometimes, but these places required tens of thousands of dollars, and insurance didn’t cover a dime. Attempts to bring about legislative changes were rarely successful, which meant draconian drug laws were still the norm, and little progress had been made in changing public perception in a society clinging to a surface-level understanding of an incredibly complex issue. Addicts were still criminalized and ostracized. Jail time was prioritized over treatment. Relapsing equated to recidivism.

A few who spoke also alluded to a kind of collectively practiced ignorance pervading modern social norms. One man, the father of two teenagers struggling with heroin addiction, lamented that there seemed to be a deliberately misconstrued understanding of heroin addicts. People were intent on seeing addicts in the most simplistic ways possible and ascribing their struggles to moral failure—they were bad eggs, all of them criminals and products of their own choices, and they deserved to be homeless and shunned, if not incarcerated. Why was it so hard for people to consider the possibility that the circumstances of someone’s life might push them toward drug use?

A woman who introduced herself as Rebecca turned out to be an actual neurologist who’d lost her daughter, Stephanie, to heroin. But not from an overdose. Stephanie had died when, after nearly a year sober, she relapsed again, and, unable to cope with the pain of disappointing the people she loved, she hanged herself. Rebecca was intent on spending the rest of her life learning how to help people struggling with the same battles that her daughter had fought. Listening to her was eye-opening.

“Addicts tend to be judged based on peripheral information: their racial, cultural, and class backgrounds, and the assumption that being an addict means being an inherently bad person,” Rebecca said, looking around as those in the circle nodded in agreement. “It’s easy to assume that only weak, spineless people resort to drugs for reckless and immoral reasons, but such naïve conclusions stem, at least in part, from the ways in which we selectively expose ourselves to the world around us. We have little incentive to engage with those who’re different from us, with people we have trouble understanding, because everything outside our comfort zone is like an unmapped wilderness, and just the mere thought of that wilderness is alarming. And in a country as polarized as ours, rifts are intensified by tribal divisions, the us-versus-them mentality associated with so many of history’s most destructive periods. A lot of people just look away when it comes to issues impacting others.”

Rebecca also explained how the addict’s plight stemmed in large part from the widespread belief that addiction was too esoteric to be addressed on a societal level. In other words, people didn’t want to understand; while they’d happily apply rational arguments to defend their misconceptions, they were unlikely to be swayed by anyone else’s rational arguments.

“Very rarely can social issues, especially the complexly human ones, be understood through abstractions or rhetoric,” Rebecca continued in her slow, intelligent way of talking that was oddly soothing. “To truly understand, you have to move up close to people, learning the macro from the micro. The problem is that people don’t like uncertainty. We don’t like it when the beliefs and assumptions we’ve long subscribed to are challenged. Nobody wants to find out they’ve been wrongly convinced of a core belief, especially when our beliefs are so heavily entwined with our identities. Even in the absence of what we know to be important information, we’d rather fill in the gaps on our own, using self-affirming information to placate ourselves. People would rather continue believing that addicts, the homeless, those struggling with mental illness — the outcasts ever-present on the outskirts of society — are just complicit denizens, thereby minimizing the complexities at the root of social issues and negating any moral pressure to empathize.”

“And if I could just add to that,” a bespectacled man said, raising a shaking finger in the air. “Beneath that addict, under that dirty and unkempt exterior, is someone who at some point in life wanted to forget something so badly, or was hurting so badly, or was so desperate that they were willing to do just about anything. I think it’s interesting that the drug problem today is mostly people using downers—opiates, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, antihistamines, and the like. Nobody’s looking to make things more fun or intense, they’re looking for a way out, a way to escape it all. Pain, heartache, loneliness, guilt, shame, sorrow—we all experience these differently, and the degree to which they affect each of us depends in large part not on our ability to cope but on the severity of the issue. Every life unfolds the same: through moments. It’s not like people are born drug addicts; they don’t come out of the womb shooting up heroin. And I think it’s real ignorant for people to mock pains they themselves have never endured, just like it’s ignorant to judge a person based on incomplete information.”

Sitting in the same circle as these normal, everyday people who were all carrying the same invisible weight and trying to deal with the same immeasurable grief was as revelatory as it was haunting. I felt oddly diminished, diminutive. Being part of this temporal group comprised of people with whom I had little to no frame of reference with made me feel angry, both at myself and at others.

I thought of Jenny. Jenny wasn’t a bad person. From what little I knew about her, I thought it was easy to understand that Jenny had become a heroin addict the same way someone develops a drinking problem: by turning to and relying on a behavior that helps you deal with pain and lets you escape. Jenny had made mistakes, of course, but who doesn’t? My life was riddled with mistakes. Personally, I didn’t believe anybody who tried to flaunt a mistake-free, success-only life, as if they were incapable of doing wrong.

After the meeting, I went back to my hotel room and reflected on everything that had been said. I even surfed around online on my phone, reading different articles and opinion pieces on the opioid epidemic. Not because I was suddenly filled with an evangelical-like zeal, convinced of everything I’d heard earlier, but because I was genuinely curious and wanted to know more.

Well, I must say that those in the medical profession carry some of the blame for prescribing meds that are addictive which was especially true in the past. My cousin's daughter became addicted to a drug whose name I already forgot and prescribed by her doctor. No doubt she was able to get other drugs, and maybe more of the one that was prescribed somewhere else. Who knows why she became addicted. Two much more attractive sisters with better marriages then her own? Overweight, taunted in school, who knows. Now she's dead with decades unlived. Her mother excused her two sisters and her husband for not going to her funeral. My cousin was wheelchair bound from a guy with Alzheimer's who drove into her car repeatedly as she waited for her younger daughter to be let out of school years before. They live in Washington and I'm on the other coast, so I couldn't be much help in that regard. They didn't go because she was addict, not their sister, but an addict, not their mother's child, but an addict. I know that helps them deal with their own bad feelings, but I don't forgive them their self protection. No friends, no other family out there. Her husband dead, so she went alone to bury her daughter.

You don't mention it but much, if not all of the increase is down to fentanyl. They used to use it just to cut heroin, but now it's in everything. It's so much more powerful than even pure heroin, it is trivially easy to get a hot load, i.e. what should be a normal dose but in reality it's way more than to kill someone.

In Canada, Vancouver has now decriminalised all drugs in attempt to stop the holocaust. The law against drugs drives up prices, stigmatises and forces people to buy fentanyl laced poison. I would argue that the war on drugs has killed more Americans than any war.

*except, perhaps, the Civil War