32 Ideas for 32 Years

Some concepts and ideas I've collected that might be of interest to you.

I recently turned 32. It’s hard to put an age on a writer who doesn’t often talk about himself, so this may or may not come as a surprise. But I’m an old 32, with a head full of gray hair, a stooped posture under an invisible rucksack too heavy for my 5’8 frame, and a soul that would be more comfortable in WWII-era America than present day.

I’m also something of a closet nerd. I do a lot of reading and I take a lot of notes (one word document is 700+ pages), keenly aware as I am that relative to many others I know very little. Over the years I’ve accrued a ton of information, and from that information I’ve collected many interesting concepts and ideas. I thought I would share 32 of these that others might appreciate.

1.) The Friendship Recession

Americans without any friends have increased 400% since 1990. The issue is especially prevalent among men. As society continues to atomize, it will only get worse.

Loneliness is arguably the number one risk factor for premature mortality. An analysis of 300,000 people in 148 studies found that loneliness is associated with a 50% increase in mortality from any cause, making it comparable to smoking 15 cigarettes a day, and much more dangerous than obesity.

2.) The Shirky Principle

Institutions will try to preserve the problems to which they are the solution.

3.) The Third Person Effect

A well-replicated finding in psychology, this is the tendency for people to overestimate the effect of “misinformation” on others, and particularly on the masses, due to the mistaken belief that they’re unusually impressionable.

4.) The Switch Cost Effect

Today, more so than ever before, people inhabit two separate worlds—one online, one off. Both regularly interrupt life with demands and notifications, so we’re constantly straddling the two. The repeated switching of attention dents working IQ by around 10 points. The “dumbing” effect is twice as much as being high on weed.

5.) Mimetic Theory of Conflict

People who are similar are more likely to fight than people who are different. That’s why civil wars and family feuds create the worst conflicts. The closer two people are and the more equality between them, the greater the potential for conflict.

6.) The Paradox of Consensus

Researchers found that when eyewitnesses unanimously agreed on the identity of criminal suspects, they were more likely to be wrong. Under ancient Jewish law, if a suspect was found guilty by every judge, they were deemed innocent. Too much agreement implied a systemic error in the judicial process.

Be wary of consensus. It can often lead to bad decisions. The more people agree, the less likely they’re thinking for themselves.

7.) The Babble Hypothesis

According to multiple studies, what best predicts whether someone becomes a leader is not their IQ, experience, or background. It’s the amount of time they spend talking. Doesn’t even matter what they say, just how much.

8.) The Never-Ending Now

The endless scroll of our social media feeds and the 24/7 news cycle blinds us to history, as we’re constantly consuming ephemeral content. The structure of the internet and the media ecosystem pulls people away from age-old wisdom.

9.) Skinner’s Law

If procrastinating, you have 2 ways to solve it: You either make the pain of inaction > pain of action, or you make the pleasure of action > pleasure of inaction.

10.) Taleb’s Surgeon

If presented with two equal candidates for a role, pick the one with the least amount of charisma. The uncharismatic one has made it to where they are despite their lack of charisma. The charismatic one got there with the aid of their charisma.

11.) Bezos Razor

If unsure what action to pick, let your 90-year-old self on your death bed choose.

12.) The Illusory Truth Effect

When we hear the same false information repeated again and again, we believe it’s true. Over three decades of research shows that repeated statements are more likely to be judged true than novel statements, and that this is the case with both plausible and implausible claims and regardless of whether or not the claims come from reliable or unreliable sources. Troublingly, this even happens when people should know better—that is, when people initially know what they’re hearing or being told isn’t true.

13.) The Promethean Gap

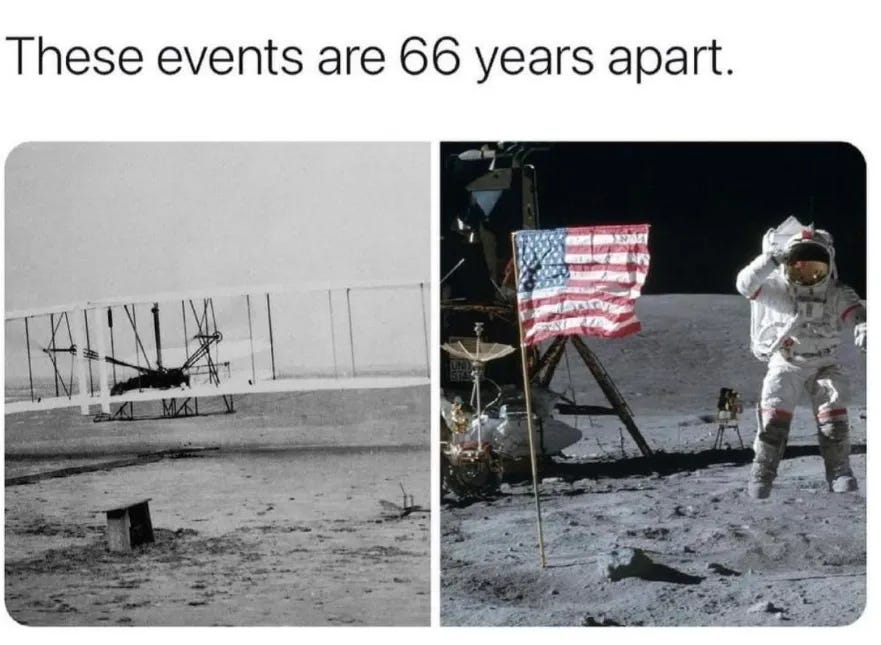

Technology is outpacing wisdom; we’re changing the world faster than we can adapt to it. Lagging ever more behind accelerating progress, we’re increasingly unable to foresee the effects of what we create.

This is related to Kurzweil’s Law: For 300,000 years, humans didn’t have computers. Then, in less than a century, we invented PCs, the web, smartphones, and generative AI. New discoveries facilitate newer discoveries, so technological progress is not linear but exponential.

14.) Gurwinder’s Third Paradox

In order for you to beat someone in a debate, your opponent needs to realize they’ve lost. Therefore, it’s easier to win an argument against a genius than an idiot.

15.) Postjournalism

What modern journalism has become. The internet’s digital tsunami of information and emancipation of authorship shattered the traditional newspaper business model and the elite-controlled dispensation that had long endowed newsrooms with a sacrosanct authority as a gatekeeper to knowledge with a monopoly over dissemination and agenda-setting. To survive, the mainstream media has pivoted from journalism to tribalism; the goal isn’t to inform readers, it’s to confirm what they already believe.

16.) Compounding

To win big, do small things consistently. Since human brains think linearly, we vastly underestimate the exponential effects of cumulative small actions. In 2005, Canadian blogger Kyle MacDonald traded his way from a paperclip to a house in just 14 transactions.

17.) St. George in Retirement Syndrome

Many who fight injustice come to define themselves by their fight against injustice, so that as they defeat the injustice, they must invent new injustices to fight against simply to retain a sense of purpose in life. (Looking at you, progressives.)

18.) Galloway’s Razor

Research suggests people enjoy possessions less than they expect, and they enjoy experiences more than they expect. In the end, people value what they did much more than what they owned. Choose adventures over luxury items.

19.) Hedonic Treadmill

Once we’ve obtained what we desire, our happiness quickly returns to its baseline level, at which point we begin to desire something else. Whatever we get, we get used to. Therefore, contentment lies not in accumulating possessions, but in relinquishing desires.

20.) Presentism

People judge history by modern standards. The Left is especially guilty of this, always judging “dead old white men” through the mores of the present, condemning them for things like owning slaves, even though owning slaves was as common back in the day as owning a car is today.

21.) The Streetlight Effect

A drunk man is searching for his keys under a streelight. He’s offered help by a police officer who finds out the drunk has actually lost them somewhere else. Asked why he’s looking under the streetlight then, the drunk responds that this is where the light is.

This is a joke used to illustrate a form of observer bias. People tend to look for information and wisdom where it’s readily available or easy to find rather than in places where the truth might actually be found. But wisdom is often found where you least want to look, or where you least expect to find it.

22.) Hanlon’s Razor

Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by stupidity. When asking why somebody did something to you, first consider whether the person is a moron who simply didn’t know what he or she was doing.

23.) Noble Cause Corruption

A form of corruption that comes in the guise of virtue. When people are convinced of the nobility of their goals, they may think the ends justify the means. This makes it particularly sinister. It’s easier to justify and legitimize immoral actions if they come from a good place in our hearts. See for example: Sam Bankman-Fried.

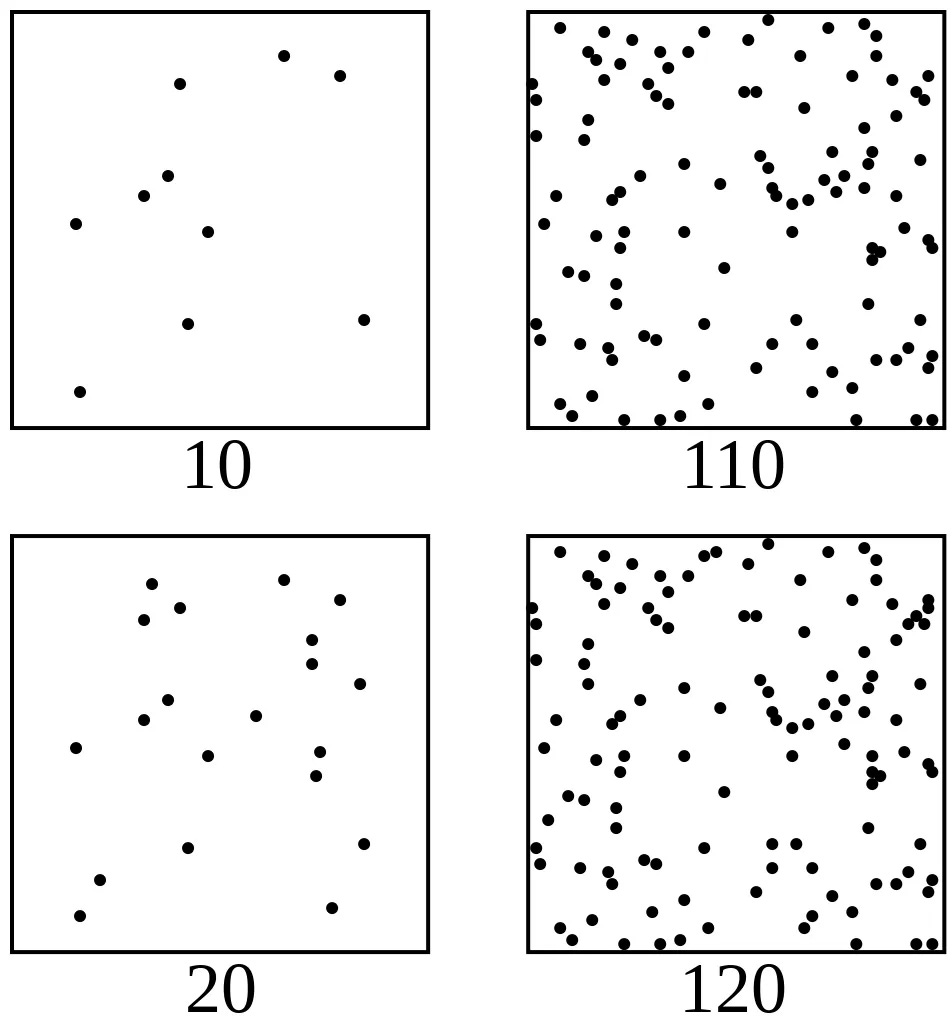

24.) The Weber–Fechner Law

Each bottom square contains 10 more dots than the one above. This is noticeable when the dots are few (left) but not when they’re many (right). This blindspot is why you don’t care about saving $100 when buying a house but you do when buying clothes.

25.) The Ellsberg Paradox

People prefer a clear risk over an unclear one, even if it’s no safer. For example, they’d rather bet on a ball picked from a mix of 50 red and 50 black balls than on one where the exact ratio of red to black balls is unknown. This helps explain market volatility.

26.) The Hock Principle

Simple, clear purpose and principles give rise to complex and intelligent behavior. Complex rules and regulations give rise to simple and stupid behavior.

27.) Postel’s Law

Be conservative in what you “send,” be liberal in what you accept. It’s a good rule for life—hold yourself to a higher standard than you hold others to.

28.) Via Negativa

When we have a problem, our natural instinct is to add a new habit or purchase a fix. But sometimes you can improve your life by taking things away. For example, the foods you avoid are more important than the foods you eat.

29.) Veblen Goods

We often attach value to things simply because they’re hard to get. People will be more attracted to a painting if it costs $3 million than if it costs $3. The price becomes a feature of the product in that it allows the buyer to signal affluence to others.

30.) The Peter Principle

People in a hierarchy such as a corporation tend to be promoted until they reach a level of respective incompetence. For example, an excellent secretary might be promoted to Director’s Assistant, which they’re not trained or prepared for—meaning they would have been more productive in their old position.

As a result, the world is filled with people who suck at their jobs.

31.) The Potato Paradox

If I have 100kg of potatoes, which are 99% water (by weight), and I let them dry until they’re 98% water (by weight), what’s their new weight?

50kg.

The truth is often counterintuitive.

32.) Dartmouth Scar

Robert Kleck, Research Professor Emeritus at Dartmouth’s Department of Psychological and Brain Scientists, had his research subjects engage in a study to test discrimination. He painted scars on some of their faces and had them attend job interviews. The participants with scars painted on their faces reported feeling discriminated against for their looks. However, unknown to them, their scars had been removed before they entered the interviews.

Some people can be victimized by the mere belief that they’re a victim.

Oh golly... these are great. I am saving to reference.

I love these human behavior principles and find most of them to be accurate.

I would add the Pareto Principle: that for many outcomes, roughly 80% of consequences come from 20% of causes (the "vital few"). Also, 20% of the problem tends to attract 80% of the effort... and thus results in 10% of the solution. Together, with the Shirky Principle, it seems to explain why none of our big social and economic problems never get solved. Doing real root-cause analysis and focusing like a laser on those causes is something we Americans seems to suck at.

By the way Brad, you are my oldest son's age, and although I think he is a smart and knowledgeable guy, I would have pegged you are being older given your collective wisdom demonstrated in your writing.

This was easily the most interesting read of the day.